The People's Bank of China (PBOC), China's de facto central bank, has made no move to stop the steady depreciation of the yuan against the U.S. dollar in a calculated move to help Chinese exporters cope with ongoing U.S. tariff hikes.

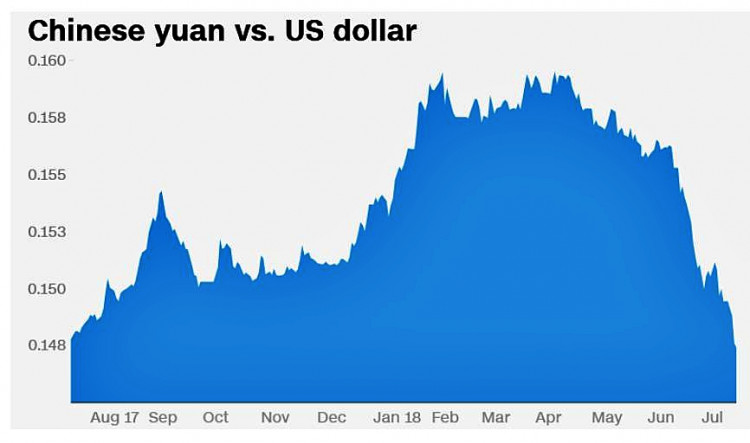

The yuan (RMB) in early trading on July 20 skidded to a 12-month low of 6.8 to the dollar, 7.6 percent lower compared to mid-February. The deterioration wasn't caused by any PBOC action, however. Financial analysts discounted trade tensions as the main factor, and instead said the drop was mostly caused by China's decelerating economic growth.

At the end of the trading day, however, the yuan reversed its early slump spurred by the PBOC's move to weaken the daily currency fixing by the most since 2016. The yuan stood at 6.7790 to a dollar at 5:36 p.m. on July 20 in Shanghai after falling as much as 0.5 percent to a new one-year low.

Analysts said dollar selling by one of the Big Four state-owned commercial banks helped reverse the morning losses. The temporary yuan recovery was also assisted by a stock surge in the afternoon session after rumors the China Banking Regulatory Commission China's, the financial regulator, might ease rules on the asset management industry

Another factor is the different direction taken by U.S. and Chinese interest rate policies. The U.S. Federal Reserve is raising interest rates and might do so twice more within the year, while Chinese regulators are forced to ease access to credit to support a decelerating economy. These divergent actions encourage investors to move money out of China and move to the U.S. for higher returns.

Experts noted the drop in the yuan's value comes at an opportune moment. It will definitely assist Chinese exporters, especially those selling to the U.S., after this country on July 6 imposed 25 percent tariffs on $34 billion of goods in a raging dispute over China's theft of intellectual property.

The decline "does provide a significant offset to the loss in export competitiveness for Chinese exporters," said British research firm IHS Markit in a report. On the other hand, a continuation of the yuan's slide will discomfit other Asian exporters such as those from Vietnam since their goods will become more expensive relative to China's.

A huge downside to the trade war is that it complicates efforts by the PBOC to make the exchange rate system more flexible, market-oriented and efficient. PBOC has fought to gradually expand the narrow band in which the yuan is allowed to fluctuate. It's also increased the margin by which the state-set daily starting price for trading can be changed.

These actions allow PBOC to intervene less often. A disadvantage to this policy is that the yuan can fall faster than regulators might want.

China hasn't deliberately depreciated the yuan's exchange rate in a decade. PBOC, however, has intervened over the past three years to keep the yuan in line with a strengthening dollar. This costly decision means PBOC is forced to spend up to tens of billions of dollars a month from China's hefty but dwindling foreign currency reserves.

PBOC apparently has more than enough monetary resources to defend the yuan, with $3.2 trillion in foreign currency serves at the end of June.