China fears that its people's genetic pool might be exploited for corporate profit. The government cracked down researchers and companies that are violating its policies on sharing its people's genetic material and information. Scientists claim that it may threaten international information collaborations.

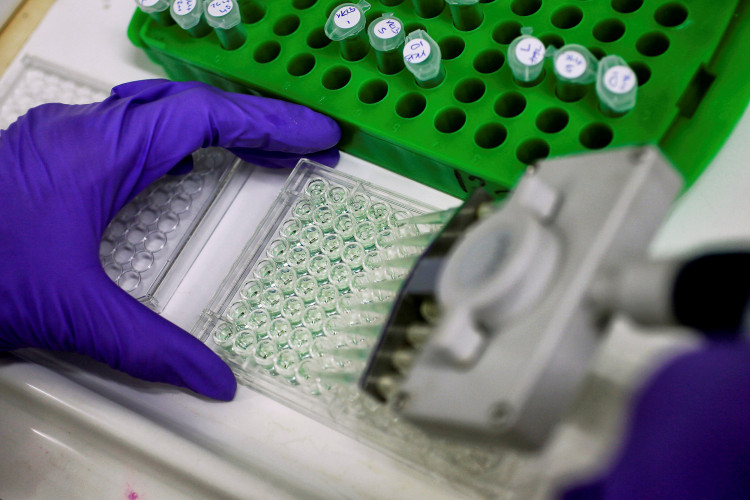

Five companies and one research hospital who violated the genetic information sharing rules were named and shamed by the ministry of science last month. The companies broke the sharing regulations that the government implemented in 1998. The companies were rebuked after they transferred human DNA samples or genetic data to other entities in the country and abroad without proper permits from the ministry's human genetic resources office.

AstraZeneca, a global pharmaceutical giant, illegally transferred samples that are used to create tests in curing breast cancer to Amoy Diagnostics in Xiamen and Kunhao Ruicheng in Beijing. The company, however, defended their actions stating that they are not aware that they need permission to transfer the material to another part of the country.

According to China's policy, they are required to file for an authorization if they want to transfer human DNA or share genetic data. They are also required to ask for permission if they are going to publish the data in international journals.

According to the ministry, the BGI in Shenzhen and Shanghai's Huashan Hospital also violated the rules after they published their data online without proper clearance. The published data is part of an international study discussing the genetics of depression which was published in Nature in 2015. The study population of the data was 10,000 or more Chinese women.

The BGI released a statement saying that they have already destroyed the data as instructed by the ministry. They also requested Nature to delete the released article from their website. However, the article is still online. Nature was unable to give a comment regarding the matter.

Worries are circulating among scientists and other experts that the crackdown might deter researchers sharing genetic data that are collected from the large genetic pool of China. Nicholas Steneck, a research integrity student at Michigan in Ann Arbor, said that at a time when transparency, open access, and sharing are high priorities, enforcing the 1998 rules obviously seems to be going in the opposite direction.

China's policy is in line with other country's control of their citizen's genetic material and information that can be collected and shared to protect its people's privacy and to ensure that sample gathering has their consent.