The United States has an unparalleled mix of low unemployment, inflation, and interest rates, and as money experts tackle new ways to improve the country's financial network, central bank officials wrestle with how to parry the next economic punch.

At a three-day conference in San Diego to address a variety of economic subjects, one stuck out: the Federal Reserve's textbook view, where low unemployment generates excessive inflation that monetary policymakers may offset with increases in interest rates, is at least badly hobbled if not broken entirely.

Not only is a low joblessness rate and weak inflation coexisting, but global interest rates are trapped at such low levels and are considered so unlikely to rise that the central bank and other finance institutions will face the next recession with little room to cut rates until they hit rock bottom and focus on other strategies.

These factors are techically 'the hand we are being dealt with," said John Williams, Federal Reserve-New York President, expressing concern shared by other central bankers and academic researchers gathered for the annual American Economic Association meeting.

The central bank is in the midst of a wide-ranging analysis of its monetary policy strategy. Now, the economy is felt to be running well, with a near-term recession unlikely - an ideal time to make adjustments, officials say.

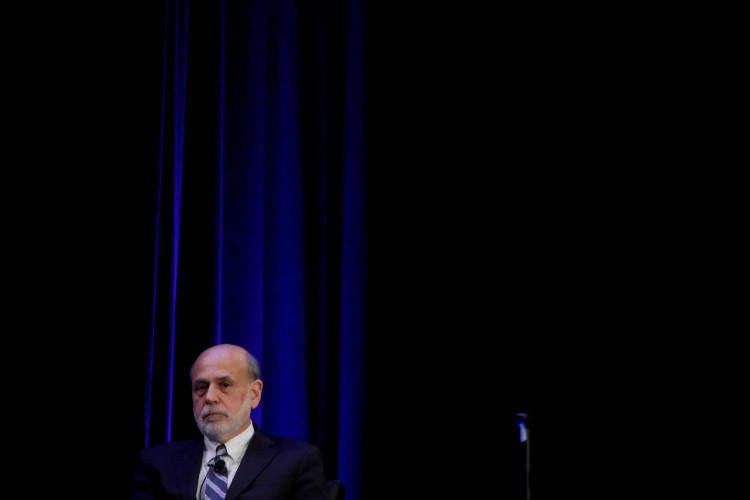

The conference created a host of proposals, including one from former Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke, to make a one-time unorthodox monetary policy methods like bond-buying a permanent part of the arsenal of the central bank.

With a target rate unlikely to rise far beyond 2 to 3 percent, and currently set lower than that, the Fed would not have ample "firepower" to battle the next downturn, officials said.

On Sunday, former central bank chairman Janet Yellen urged for better financial regulation tools, and suggested that the Fed could safely leave low-level interest rates, improve employment and wage growth if it was assured that other approaches could be used to ensure that a continuing period of easy money would not contribute to a credit crisis.

Though it may be a somewhat sensitive matter in the United States, other countries have actually put more stringent limits on mortgage credit to avoid encouraging risky borrowing.

Federal Reserve-Cleveland President Loretta Mester told Reuters on the sidelines of the conference that if central bank policymakers try to resolve one question in their minds right now, it's just how much financial risk they are willing to push into the future in exchange for the benefits that employees see today.