Hunger is still a huge problem even in the 21st century, a crisis that's been amplified by the coronavirus pandemic. But satellites have a way of providing pertinent info about food security, monitoring crop growth in order to alleviate the situation.

According to a recent report from the World Food Progamme, over 130 million more people could be driven into chronic hunger by the end of 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The ongoing health crisis has caused disruptions in the food supply chain, including the availability of crops, cross-border trade, transport, and limitations in labor.

Understanding the impact of the pandemic on agriculture is important in order to weaken the uncertainty in the food supply chain. Staple crops are already very much limited due to lack of labor shortages of fertilizer, and issues related to national export. All these contribute to the availability of food in the future.

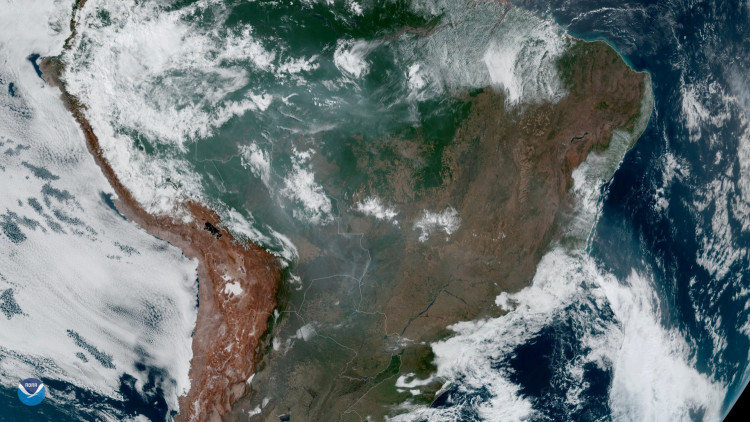

This is where satellites come into play. With these advanced monitoring tools, we can gather info regarding planting and harvesting in order to secure our sources of food.

NASA, ESA, and the Japanese Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) recently collaborated to launch the COVID-19 Earth Observation Dashboard, a program that consolidates satellite data to monitor the worldwide impact of the pandemic, including in the agricultural sector.

The platform hosts numerous analyses regarding food production, including this recent study involving winter cereals in Spain. The country has approximately 2 million hectares of winter cereal plantation mostly found in the regions of Aragon, Castilla-la-Mancha, Andalucia, and Castile and León. Satellite data has allowed for near real-time monitoring of harvests at parcel-level in the whole of Spain.

Researchers from the Université Catholique de Louvain (UCL) in Belgium used data from the Landsat 8 mission and the Copernicus Sentinel-1 and Sentinel-2 missions and combined it with machine learning in order to monitor crops weekly.

Compared to last year's data, the team found that the 2020 harvesting season began in mid-June, which is delayed in terms of the average crop calendar winter cereals in Spain.

The National Spanish Agrarian Guarantee Fund (FEGA) has expressed its support for the monitoring work and worked with UCL to analyze the results. They found that while the coronavirus pandemic contributed to the delayed harvest, part of it was caused by the weather as well.

"Satellite indicators demonstrate the capabilities of monitoring the planting, growth, and harvest of staple crops such as cereals and rice at national scales," said Benjamin Koetz, a seasoned Earth observation application engineer at ESA.

"These data are vital in providing timely and transparent information on agricultural production during the COVID-19 outbreak and recovery."