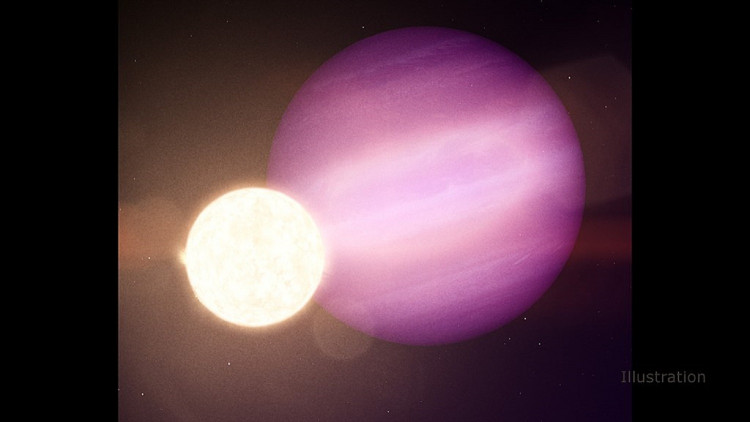

The first accurate portrait of an exoplanet has been created by Europe's new space telescope, and it found one that even planetary scientists deemed so strange.

The Characterizing Exoplanet Satellite, dubbed CHEOPS, was launched by the European Space Agency (ESA) in December; the spacecraft started scientific observations in April. CHEOPS is not meant to locate alien worlds, but rather to educate scientists so that they can create planet portraits. And scientists on the CHEOPS mission have done just that in the first reported findings of the study, creating a clear image of the planet WASP-189b, which was first observed in 2018.

The CHEOPS findings indicate that a strange planet orbiting a peculiar star is WASP-189b. Scientists had a hunch that might be the case, which is why mission scientists decided so early in the career of the spacecraft to observe the planet. The star is superhot, so hot it looks blue, and it so near its planet too that a complete orbit happens in just 2.7 Earth days.

"Only a handful of planets are known to exist around stars this hot, and this system is by far the brightest," Monika Lendl, an astrophysicist at the University of Geneva in Switzerland and lead author of the new study, said in the same statement. "WASP-189b is also the brightest hot Jupiter that we can observe as it passes in front of or behind its star, making the whole system really intriguing."

In March, April, and June, CHEOPS examined WASP-189, capturing the planet passing behind its star four times and twice in front of the star. Scientists determined some core features of the system from that information.

At around 5,800 degrees Fahrenheit, the researchers found that the planet was pretty toasty, so hot that even iron would transform to gas. Scientists have now measured the size of the planet: around 1.6 times Jupiter's radius.

The latest CHEOPS observations have taught scientists much about the star of WASP-189; it is not completely circular, but at its equator, it is wider and colder than at the poles, making the star's poles look brighter. It spins around so fast that at the equator, it's being pushed outward. On its surface, the star also tends to have brighter and darker spots.

WASP-189b circles the star at a radical tilt, taking it close to the star's poles, unlike in our solar system, where planets orbit along the sun's equator. The strange feature makes scientists think that the planet may have developed far farther away from the star, then moved the planet inward and askew by some strong gravitational force, maybe another star.

The scientists at the CHEOPS mission agree that this kind of work is exactly what the telescope was intended to do: take a known exoplanet and give a more accurate view of the world to scientists.

A paper describing the research is set to be published in the journal Astronomy & Astrophysics.