A remarkable discovery by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration's Curiosity rover reveals that some sections of Mars have had their history entirely deleted.

The key objective of the Curiosity mission is to analyze Mars' historical potential for habitability, whereas the newly arrived Perseverance mission seeks actual traces or indications of ancient life.

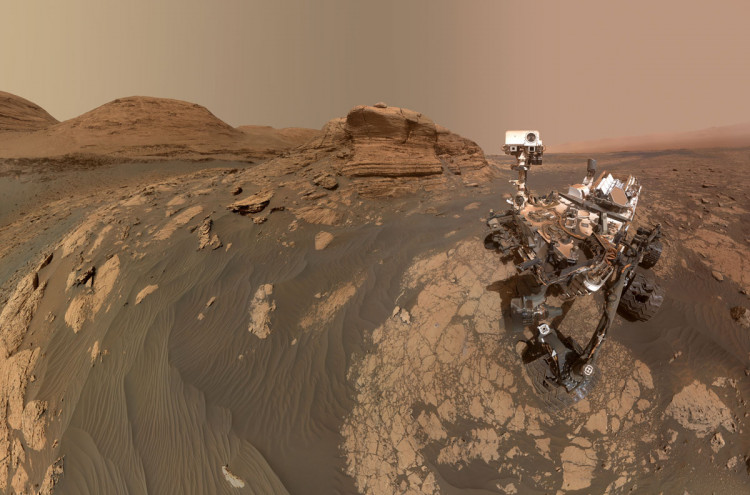

Curiosity has been studying sedimentary rocks in Gale crater that are rich in clay minerals to that end. Clay is a significant indicator of habitability because it indicates the presence of liquid water-a necessary component for life. It's also a great material for preserving microbial fossils.

Curiosity took two samples of ancient mudstone, a sedimentary rock containing clay, from patches of the dried-out lake bed that were dated to the same time and place (3.5 billion years ago and only 400 meters apart).

Researchers then discovered that one patch only contained half the expected amount of clay minerals. Instead that patch included a higher concentration of iron oxides, the components that give Mars its rusty tint.

The research believes brine is to blame for the geological disappearance: super-salty water that infiltrated into the mineral-rich clay layers and destabilized them, draining them away and wiping sections of the geological - and potentially even biological - record clean.

According to the research, this process was not uniform across the bottom of the former lake since it occurred after the lake lost its liquid water. Groundwater in Gale crater continued to flow beneath the surface, transporting and dissolving compounds.

As a result, several underlying mudstone pockets were exposed to varying conditions. Those regions exposed to salty water went through a process known as "diagenesis," in which changing mineralogy erased the geological-and potentially biological-record.

"We used to think that once these layers of clay minerals formed at the bottom of the lake in Gale Crater, they stayed that way, preserving the moment in time they formed for billions of years," study lead author Tom Bristow, a researcher at NASA's Ames Research Center in Mountain View, California, said in a statement.

"But later brines broke down these clay minerals in some places - essentially resetting the rock record."

The researchers published their findings in the journal Science.