A 3.3-foot-long (1-meter) sea scorpion roamed the seas of what is now China 435 million years ago, ensnaring prey with its massive, spiny arms.

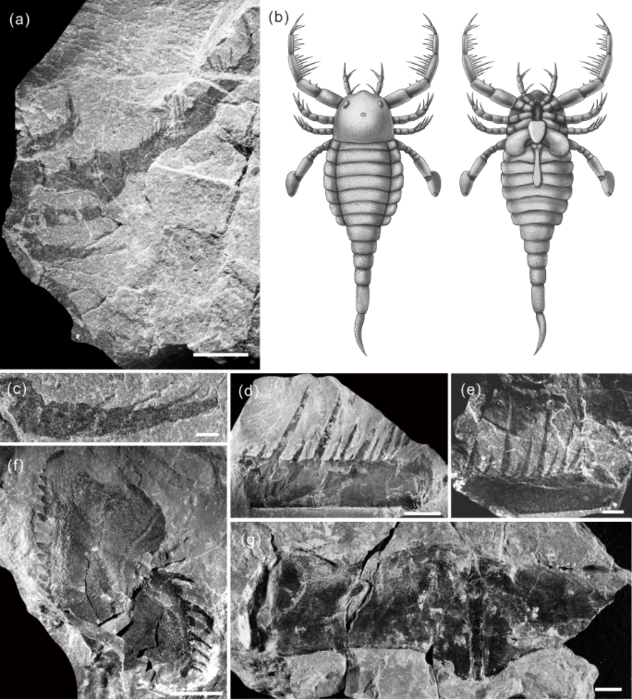

The remains of this scorpion (Terropterus xiushanensis), which was a eurypterid - an ancient arthropod closely related to current arachnids and horseshoe crabs - were recently unearthed by archaeologists, according to a report published in the journal Science Bulletin.

"Our knowledge of mixopterids is limited to only four species in two genera," professor Wang Bo from the Nanjing Institute of Geology and Palaeontology of the Chinese Academy of Sciences said in a statement, "which were all based on a few fossil specimens from the Silurian Laurussia 80 years ago."

Eurypterids came in a variety of sizes, with the smallest being approximately the size of a human hand and the largest being the size of an adult human.. T. xiushanensis, the newly described species, is the first Mixopteriade family member discovered in 80 years, according to the researchers.

The discovery adds to our knowledge of the worldwide spread of megafauna and their enormous biological diversity.

The terrifying beast lived between 443.8 million and 419.2 million years ago, during the Silurian period. In their underwater stalking grounds at the time, scorpions would have been the apex predators, pouncing on unsuspecting fish and mollusks, scooping them up in their pedipalps, and shoving them into their mouths.

T. xiushanensis is also the first mixtopterid to be identified in what would have been Gondwana, the supercontinent formed when Pangaea split in two.

While a dog-sized scorpion is an eye-catching find in the fossil record, there are all kinds of outrageously big critters that would seem like something out of a horror film if they walked the earth or prowled the waters today.

This is surprising in many ways, because evolution has traditionally attempted to minimize a species' physical body mass as much as possible, because the larger something is, the more energy and work the body must perform to support itself.

It's unclear why nature allows for such gigantic creatures, but it's thought that they evolved during a colder, more glacial epoch and gradually died out as the Earth's climate warmed over time.