According to a recent study, giant cyclones that form around Jupiter's poles are caused by the same forces that move water in Earth's oceans.

Jupiter's massive polar cyclones, which may span up to 620 miles (1,000 kilometers), were discovered in 2016 by NASA's Juno probe. Since then, scientists have believed that these storms are caused by convection, the process by which hotter air expands and rises to higher, colder, and denser altitudes on Earth. They could not, however, verify the occurrence of this process on Jupiter.

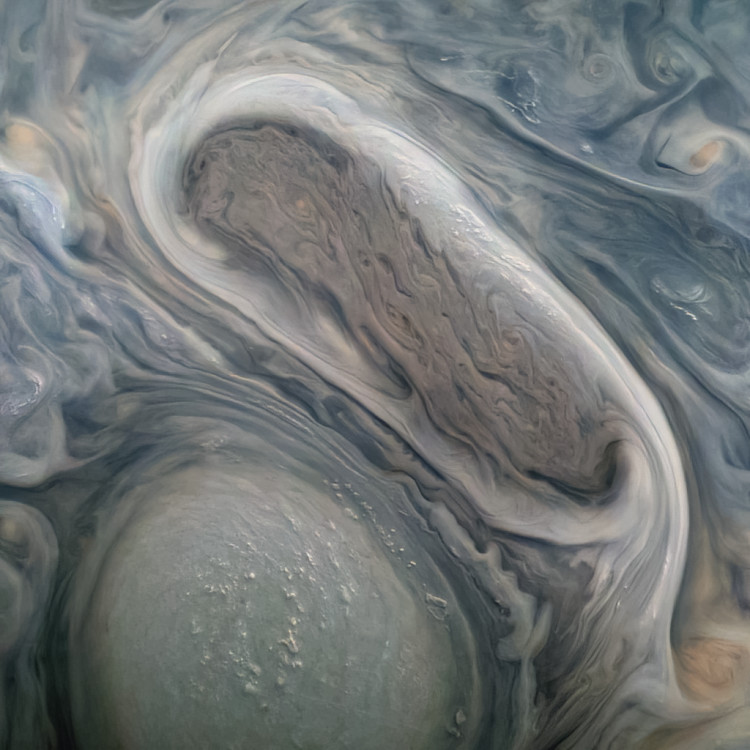

However, comparing satellite images of marine phytoplankton blooms on Earth to images of atmospheric turbulence near Jupiter's poles can be tricky -- they look remarkably similar.

Moist convection is the source of Jupiter's amazing turbulence, and it's this startling likeness that has ultimately led us to an answer. This is when warmer, less dense air rises, and even at the tiny scale, it's enough to generate enormous cyclones on our Solar System's biggest planet.

Interestingly, it took an ocean scientist to figure out what was going on.

"When I saw the richness of the turbulence around the Jovian cyclones with all the filaments and smaller eddies, it reminded me of the turbulence you see in the ocean around eddies," oceanographer Lia Siegelman of Scripps Institution of Oceanography, said.

"These are especially evident on high-resolution satellite images of plankton blooms for example."

Siegelman and her colleagues analyzed a series of images of Jupiter's north pole cyclones captured at infrared wavelengths, which reveal the heat emitted by an item. The researchers utilized the same methods that scientists use to investigate large-scale air and water fluxes in the Earth's atmosphere and seas.

The research allowed the scientists to calculate the direction and speed of local winds as well as track cloud migration. The researchers were able to tell the difference between locations with little cloud cover, where they could see further into Jupiter's atmosphere, and areas hidden by a dense layer of fog.

Rising hot air moves energy within the atmosphere and feeds clouds as they build into large-scale cyclones, such as those seen around the poles, according to the study.

This discovery began with Earth and a startling resemblance between our home planet and Jupiter. It also boomerangs back to Earth: it could be able to provide some insights into our own atmospheric processes, the researchers said. Wind data on Earth have a kinetic energy spectrum that is comparable to that of Jovian observations, implying that both planets are transferring energy in a similar way.

The team's research has been published in Nature Physics.