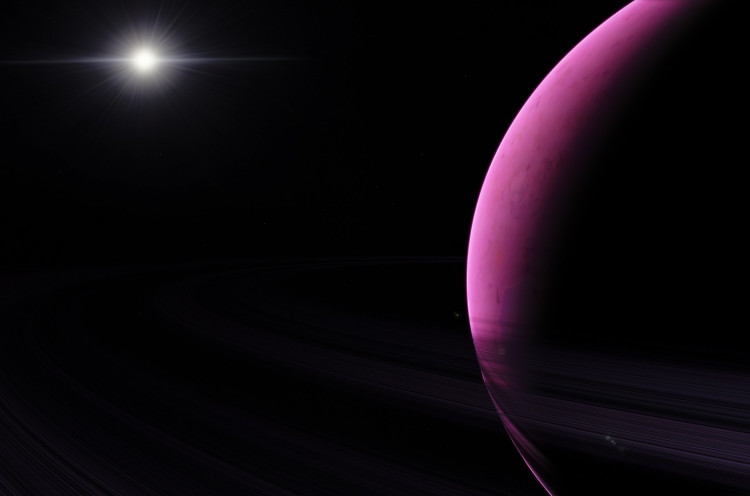

Instead of the usual sphere, a team of astronomers examining faraway exoplanets discovered one that appears to be shaped like a football-or a rugby ball, depending on your perspective.

According to a new study, the odd shape of ultrahot WASP-103b, which is more than 1,000 light-years away from Earth, is due to the planet being stretched by the gravitational forces of its host star.

WASP-103b was found in 2014. The exoplanet is classified as a "hot Jupiter" because it circuits its parent star in a single Earth day, putting it in close proximity to the star's radiation and strong gravity. According to a statement from the University of Geneva, the powerful tidal pressures created on the planet are similar to the tides induced by the moon in our oceans on Earth, but considerably more extreme.

"Because of its great proximity to its star, we had already suspected that very large tides are caused on the planet, but we had not yet been able to verify this," study co-author Yann Alibert, professor of astrophysics at the University of Bern in Switzerland, said in the statement.

The CHaracterizing ExOPlanets Satellite (CHEOPS), a European space telescope that launched in December 2019, made the latest observations.

Previous observations by NASA's long-running Hubble Space Telescope and the now-retired Spitzer Space Telescope, which acquired data during numerous "transits," or passing of the planet across the face of its star from Earth's perspective, were also utilized by the researchers'.

The transits also allowed scientists to investigate the planet's interior, which they believe is similar to Jupiter's in our solar system. WASP-103b mass is distributed using a parameter called a "Love number" (named after British mathematician Augustus E. H. Love), yet the researchers found that further observations are needed to pin down the value.

Future studies of WASP-103b by the recently launched James Webb Space Telescope, according to the team, could provide better limitations on the planet's radius. Webb, which successfully deployed its primary mirror this week, is continuing on its way to its observation location in space.

The scientists underline that this would increase our understanding of these so-called hot Jupiters and allow for a better comparison between them and massive planets in the solar system.

The new research was published in Astronomy and Astrophysics in January 2022. Susana Barros, a researcher from Portugal's Institute of Space Astrophysics and Science, was in charge of the project.