A new Trojan asteroid has officially joined Earth in its orbit around the Sun.

Trojan asteroids are asteroids (also known as minor planets) that share the orbital path of larger planetary bodies. While we have discovered Trojan asteroids orbiting other planets in our solar system and others, only one of these objects, 2010 TK7, has been confirmed to orbit Earth.

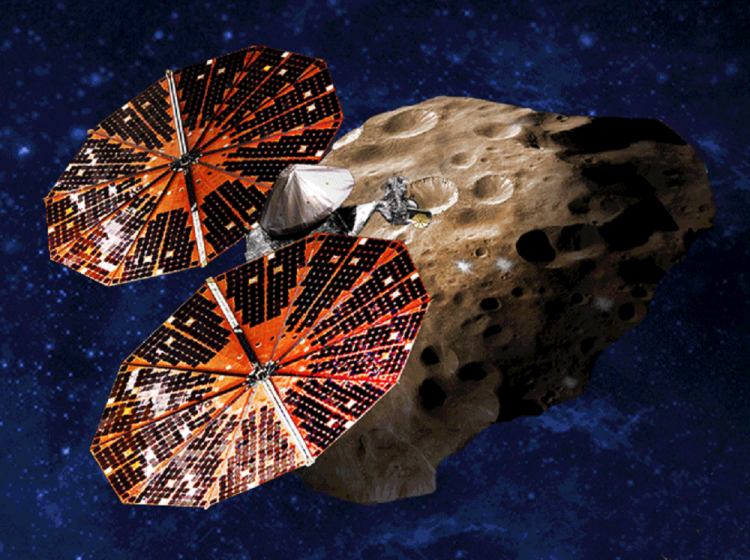

In a new study, experts determined that the asteroid 2020 XL5, discovered in 2020, is the second of its kind, known as an Earth Trojan asteroid. Consider it an extra companion to Earth, although a very small one.

"The discovery of 2020 XL5 as an Earth Trojan, confirms that 2010 TK7 is not a rare exception and that there are probably more," study lead author Toni Santana-Ros, a researcher at the University of Alicante and the Institute of Cosmos Sciences (ICCUB) at the University of Barcelona (IEEC-UB), told Space.com. "This encourages us to keep enhancing our survey strategies to find, if exists, the first primordial Earth Trojan."

Astronomers estimate that 2020 XL5 will stay around for at least 4,000 years before speeding off to regions unknown, just like the first Trojan.

2020 XL5 was discovered in December 2020 by astronomers using the Pan-STARRS 1 survey telescope in Hawaii, and was added to the Minor Planet Center database of the International Astronomical Union. Using NASA's publicly available JPL-Horizon software, amateur astronomer Tony Dunn calculated the object's trajectory and discovered that it orbits L4, the fourth Earth-sun Lagrange point, a gravitationally balanced zone surrounding our planet and star. The first-confirmed Earth Trojan asteroid, 2010 TK7, is likewise near L4.

However, the orbit of 2020 XL5 around the sun was not well understood at the time, so it was unclear whether the object was simply a local space rock crossing Earth's orbit or if it may be a genuine Earth Trojan asteroid.

A team led by Santana-Ros studied the object with the SOAR (Southern Astrophysical Research) Telescope in Chile, the Lowell Discovery Telescope in Arizona, and the European Space Agency's Optical Ground Station in Tenerife, Canary Islands, to confirm whether or not it is an Earth Trojan asteroid.

Any object orbiting the Lagrangians would move a lot, leaving a huge patch of sky to scan for relatively small objects; having two Earth trojans to analyze will provide astronomers a larger toolkit for estimating their orbits.

As a result, we may be able to locate a population of hundreds of Earth trojans lurking in the shadows.

The team's research has been published in Nature Communications.