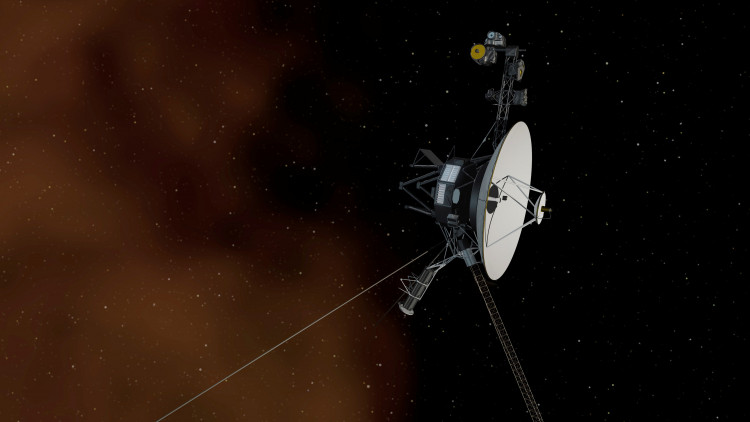

NASA's Voyager 2 spacecraft launched into space on August 20, 1977. Voyager 1 was launched 16 days later. They are not only the most distant man-made objects from Earth, at 12 billion and 14.5 billion miles (19.3 billion and 23.3 billion kilometers), respectively, but also NASA's longest-running mission, continuing to send back data from their interstellar journeys as they approach their 45th birthdays.

However, the finite nuclear energy sources that power each Voyager spacecraft are depleting to dangerously low levels. Three radioisotope thermoelectric generators on each spacecraft use the energy released during the radioactive isotope plutonium-238's decay to generate electricity (RTGs). The RTGs delivered 450 watts of power to each spacecraft upon launch. Their electrical output is declining by four watts a year and they are currently producing less than half that amount.

"We're at a power level currently where we only have about five to six watts of power margin on each spacecraft," said Suzanne Dodd, project manager for the Voyager Interstellar Mission and director of the Interplanetary Network Directorate at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in California. "It takes about 200 watts, approximately, to run the transmitter on the spacecraft, to be able to send signals back to Earth."

But the show hasn't ended yet. By selectively turning off some subsystems on both Voyager spacecraft, such as heaters, the Voyager teams have been able to conserve power and keep others running longer. Surprisingly, the surviving scientific equipment is functioning effectively so far despite the chilly conditions. In terms of running the instruments cold, Dodd stated, "It's great that we get data far beyond what we thought we could."

The Voyager instrument teams will get together this summer in between the launch anniversaries of each spacecraft to share their most recent findings. The combined data serve as the basis for a new model that will direct future plans for both spacecraft, including any instrument shutdowns.

According to Dodd, the spacecraft might continue to operate for another five years using energy conservation techniques. "And if we got really lucky, maybe doing some operating below some thresholds, we might be able to go out to the 2030s," she said.

As both Voyagers get older, it's projected that these anomalies will appear. Even if a spacecraft has power, a malfunction might ultimately cause it to lose contact with Earth. Nevertheless, the Voyager mission has already been a huge success, regardless of how long Voyager 1 and 2 remain in operation.