Even though the James Webb Space Telescope has only been in operation for a few weeks, its initial findings are impressive.

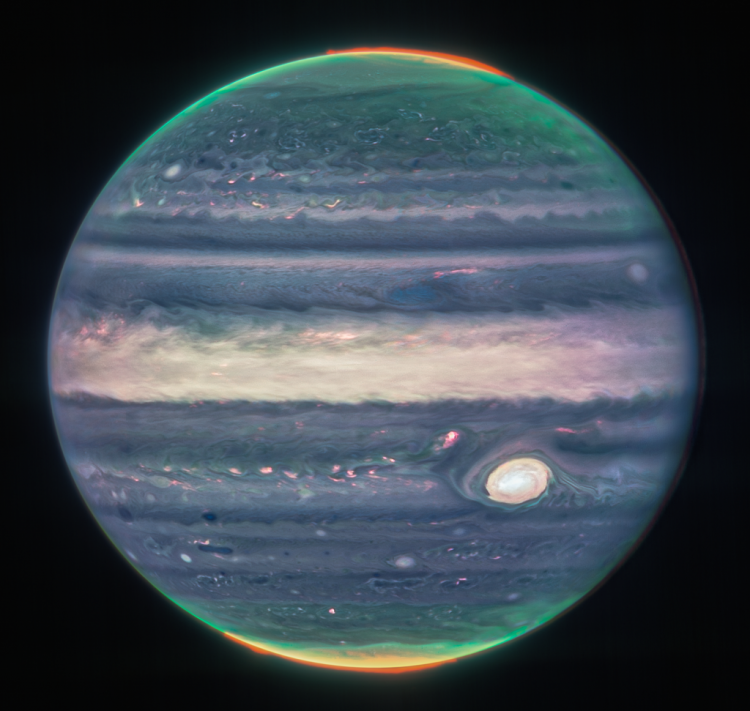

The most recent photographs of Jupiter to be released by the James Webb Space Telescope team reveal the planet's auroras surrounding its poles in two incredibly detailed images. Both pictures are composites, which means they bring together a number of low-resolution shots acquired with the telescope's Near Infrared Camera (NIRCam) using various filters into a single, high-resolution picture.

Amalthea is the brilliant dot on the far left of the wide-field view, while Adrastea is the faint dot at the border of the rings, situated between Amalthea and Jupiter. You can also see Jupiter's faint rings and two of its moons. Galaxies are thought to be the faint spots of light behind the three heavenly bodies.

"We hadn't really expected it to be this good, to be honest," planetary astronomer Imke de Pater, professor emerita at the University of California, Berkeley, said in a statement. As part of Webb's Early Release Science initiative, De Pater co-led these observations of Jupiter with Thierry Fouchet, a professor at the Paris Observatory. "It's really remarkable that we can see details on Jupiter together with its rings, tiny satellites, and even galaxies in one image," she added.

The Great Red Spot and the equatorial region both have high-altitude hazes, according to Heidi Hammel, Webb interdisciplinary scientist for solar system observations and vice president for science at AURA. The numerous bright white "spots" and "streaks" are probably very high-altitude cloud tops from condensed convective storms, according to the research.

You might be curious as to why the colors in the photographs differ from what we are accustomed to seeing while discussing Jupiter. Because Webb sees light in the infrared spectrum rather than the visible spectrum, the two photos' hues are different from what our eyes can see. These photographs are not "true-color," but rather "false-color," because the infrared data has been mapped onto the visible light spectrum.

And that raises an interesting point on how Webb truly functions. Scientists simply receive raw data that indicates brightness as detected by Webb's receptors when Webb "takes an image"-it isn't actually taking a picture and sending it back to Earth. Thus, in order to produce the photos, scientists must process the data.

Usually, the Space Telescope Science Institute (STScI), with its headquarters in Baltimore, is in charge of doing such. However, Judy Schmidt of Modesto, California, a citizen scientist, analyzed the data in the instance of this pair of Jovian photos. She worked with Ricardo Hueso, a co-investigator on the observations from the University of the Basque Country in Spain, on the wide-field photograph.