Researchers in Spain have decoded the genetic code of the immortal jellyfish, an organism that can repeatedly revert to a juvenile state, in an effort to discover the mechanism behind their extraordinary longevity and uncover new information about human aging.

The genetic sequence of Turritopsis Dohrnii, the only known species of jellyfish capable of repeatedly reverting back into a larval stage after sexual reproduction, was mapped by Maria Pascual-Torner, Victor Quesada, and colleagues at the University of Oviedo in their study, which was published on Monday (Aug. 29) in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

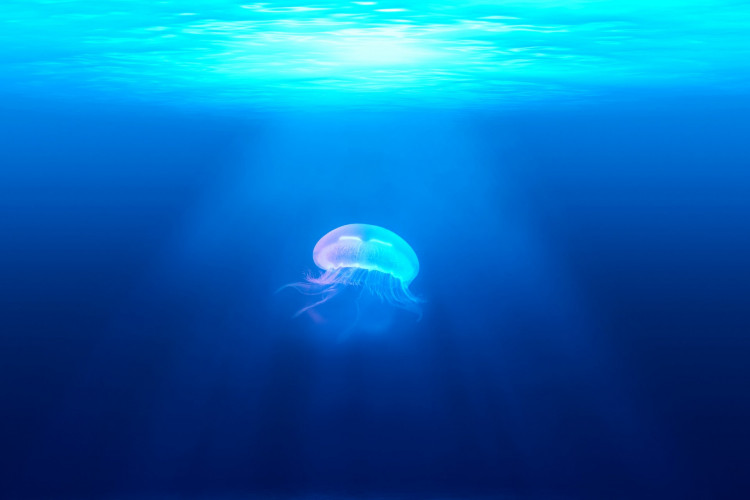

Like other varieties of jellyfish, the T. Dohrnii has a two-stage life cycle, spending its asexual phase on the ocean floor where its main objective is to survive during periods of food scarcity. Jellyfish can reproduce sexually if the conditions are favorable.

Although many different kinds of jellyfish may slow down time and return to a larval stage, most of them lose this ability once they reach sexual maturity, according to the authors. But not in T. Dohrnii.

"We've known about this species being able to do a little evolutionary trickery for maybe 15-20 years," Monty Graham, a jellyfish expert, and director of the Florida Institute of Oceanography, who was not involved in the research, said. This method gave the species the label "immortal jellyfish," which Graham acknowledges is a bit of an exaggeration.

By comparing the genetic sequence of T. Dohrnii to that of Turritopsis Rubra, a near genetic relative that is incapable of rejuvenation following sexual reproduction, the scientists sought to understand what made this jellyfish unique.

They discovered that T Dohrnii contains mutations in its genome that may improve its capacity for DNA copying and repair. Additionally, they seem to be more adept at protecting telomeres, which are the ends of chromosomes. Telomere length has been demonstrated to decrease with aging in humans and other species.

Graham claimed that the study has no immediate use in industry.

"We can't look at it as, hey, we are going to harvest these jellyfish and turn it into a skin cream," he said. "It's one of those papers that I do think will open up a door to a new line of study that's worth pursuing."

Holding T. Dohrnii is quite challenging to keep in captivity. Currently, just one scientist, Shin Kubota from Kyoto University, has managed to sustain a group of these jellyfish for a sustained period of time.