The World Health Organization (WHO) and leading scientists are sounding the alarm about a highly dangerous new strain of mpox rapidly spreading in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). With escalating cases and fatalities, there are rising concerns about potential international spread.

The newly identified strain, known as Clade 1b, shows particularly severe symptoms and higher mortality rates compared to previous strains. "There is a critical need to address the recent surge in mpox cases in Africa," said Rosamund Lewis, WHO's technical lead for mpox, during a recent briefing.

Jean Claude Udahemuka, a researcher from the University of Rwanda working in South Kivu province, where the outbreak is centered, emphasized the gravity of the situation. "It is undoubtedly the most dangerous so far of all the known strains of mpox," he stated, urging the international community to prepare and support local response efforts.

According to Cris Kacita, head of the DRC's mpox control program, the country has reported approximately 8,600 cases of mpox this year, resulting in 410 deaths. This outbreak is the most severe the region has seen, affecting 24 out of the DRC's 26 provinces.

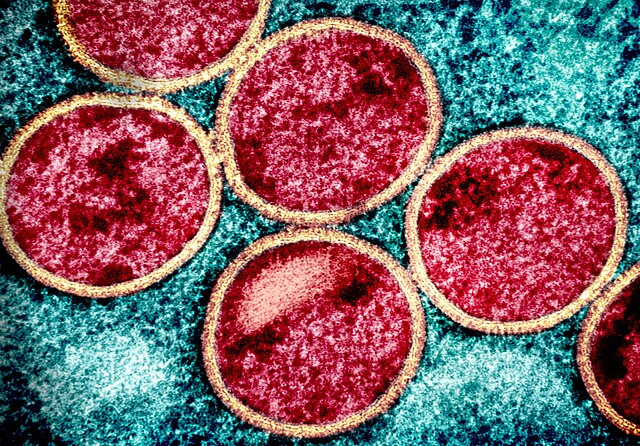

Mpox, a viral infection that spreads through close contact, causes flu-like symptoms and pus-filled lesions. While many cases are mild, the new Clade 1b strain has proven lethal, with a fatality rate of around 5% in adults and 10% in children. This is a significant increase from the less severe Clade 2 strain, which caused a global outbreak in 2022 but had a mortality rate of less than 0.5%.

In South Kivu, the epicenter of the current outbreak, the virus has spread rapidly among sex workers and through sexual contact. However, it is also spreading through other close contact routes, including within households and schools, as noted by Udahemuka and his colleagues.

Leandre Murhula Masirika, research coordinator in South Kivu, reported that around 20 new cases are being admitted to hospitals in the mining town of Kamituga each week. He expressed concern about the potential for the virus to spread beyond the DRC. "At the rate things are going, we risk becoming a source of cases for other countries," he warned.

The WHO has highlighted the lack of available vaccines and treatments in the DRC as a major obstacle in controlling the outbreak. While vaccines were used to combat the Clade 2 outbreak globally, they are not currently available in Congo. Efforts are underway to address this gap, with plans for an emergency vaccination campaign in South Kivu.

The spread of Clade 1b has also prompted fears due to its severe symptoms. Unlike the Clade 2 strain, which primarily caused localized rashes, Clade 1b often results in widespread rash, miscarriages in pregnant women, and other long-term health issues. The virus's ability to cause severe blister-like rashes and its potential for person-to-person transmission raise significant public health concerns.

"We are very afraid [Clade 1b] is going to cause more damage in terms of health importance," Masirika said. He noted that while the new cases are predominantly sexually transmitted, the virus has also been seen to jump between household members and has caused at least one outbreak among schoolchildren.

The international community is closely monitoring the situation, with genetic sequencing being conducted to better understand the new strain. "There is an urgent need to better understand the new strain," said Trudie Lang, professor of global health research at the University of Oxford. She stressed the importance of learning more about the virus's incubation period and its potential to spread without symptoms.