A federal judge has blocked a Louisiana law mandating that public K-12 schools and state-funded university classrooms display the Ten Commandments, ruling the requirement unconstitutional. U.S. District Judge John W. deGravelles issued a preliminary injunction Tuesday, stating that the law's overtly religious intent conflicted with the First Amendment's prohibition on government establishment of religion.

The ruling came in response to a lawsuit brought by a coalition of parents, represented by civil liberties organizations, who argued that the legislation would impose a religious message on their children. "This ruling should serve as a reality check for Louisiana lawmakers who want to use public schools to convert children to their preferred brand of Christianity," said Heather Weaver, a senior staff attorney for the ACLU's Program on Freedom of Religion and Belief.

Louisiana Attorney General Elizabeth Murrill, who, along with Governor Jeff Landry, supported the law, vowed to appeal. "We strongly disagree with the court's decision," Murrill said, expressing hopes that the 5th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals in New Orleans would overturn the ruling. The state plans to argue that the Ten Commandments' historical significance justifies its mandated display, not solely its religious content.

Judge deGravelles rejected this rationale, stating, "The law is 'facially unconstitutional' and 'in all applications,'" emphasizing that no secular documents such as the Constitution or the Bill of Rights were similarly required to be posted. He underscored that public school students, compelled by law to attend school, would become a "captive audience" to religious doctrine.

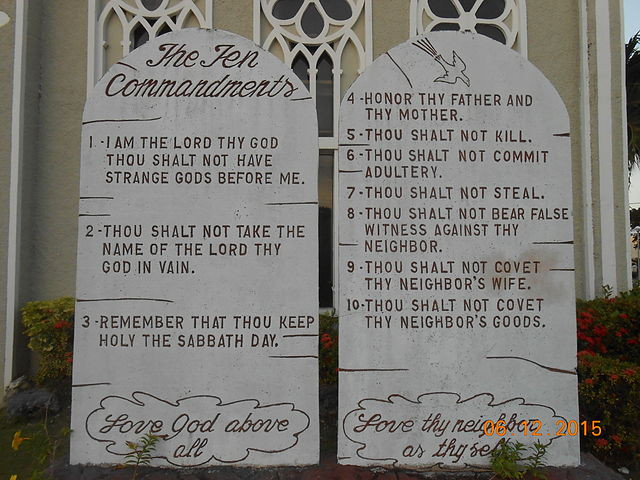

The legislation, enacted by Louisiana's GOP-controlled legislature earlier this year, called for posters or framed documents featuring the Ten Commandments to be prominently displayed in classrooms. The mandated displays were to be accompanied by a context statement noting the historical influence of the commandments on American public education. Proponents claimed that private donations, rather than public funds, would cover the cost of the posters.

The plaintiffs, a group of Louisiana parents from diverse religious backgrounds, contended that the law violated their rights to raise their children according to their beliefs without government intrusion. The Rev. Darcy Roake, one of the plaintiffs, expressed relief at the ruling. "We expect our children to receive their secular education in public school and their religious education at home and within our faith communities," she said.

Judge deGravelles cited the Supreme Court's 1980 decision that struck down a similar Kentucky law as unconstitutional. Louisiana's legislation, he wrote, constituted an impermissible endorsement of religion. "The question is not whether the Biblical laws can ever be put on a poster; the issue is whether, as a matter of law, there is any constitutional way to display the Ten Commandments in accordance with the minimum requirements of the Act," deGravelles noted. "In short, the Court finds that there is not."

Murrill and Landry defended the law as constitutional, presenting examples of how the Ten Commandments could be framed with historical context. During a press conference in August, they displayed proposed posters that drew connections between figures such as Moses and civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr., and included cultural references like a "Hamilton"-inspired rendition of the commandments.

Critics, including Steven Green, a law, history, and religious studies professor at Willamette University, testified that such efforts did not overcome the law's fundamental religious intent. "The Ten Commandments are not at the core of the U.S. government and its founding," Green argued, emphasizing the Founding Fathers' commitment to separating church and state.

The American Civil Liberties Union, the Freedom From Religion Foundation, and Americans United for Separation of Church and State supported the lawsuit, asserting that government-endorsed religious displays alienate non-Christian students and undermine public education's neutrality.

Murrill acknowledged that the court order would impact only five specific school boards named in the lawsuit-East Baton Rouge, Livingston, St. Tammany, Orleans, and Vernon parishes-leaving 67 other districts technically unaffected for now. However, she conceded that the ruling could have a "chilling effect" on any attempts to enforce the law elsewhere.

Governor Landry, a vocal proponent of the legislation, dismissed concerns from parents about religious displays in classrooms, suggesting in August, "Tell your child not to look at them." Similar legal battles are unfolding in states like Oklahoma, where a requirement to incorporate the Bible into public school curricula has sparked lawsuits.