The measles outbreak sweeping across West Texas and eastern New Mexico has now surpassed 300 confirmed cases, making it the largest in the United States this year and surpassing last year's nationwide total. Health officials are increasingly concerned that the outbreak, centered in rural areas with low vaccination rates, could spread to more populated regions as travel increases in the coming months.

The outbreak's epicenter lies in Gaines County, Texas, an area with one of the state's highest vaccination exemption rates-14% of children are exempted from immunization requirements. Two deaths have been reported since the outbreak began in late January. According to doctors, the actual case count may be significantly higher than reported, with experts warning that the confirmed cases likely represent only a fraction of total infections.

"What the true value is, I think is still hard to determine right now," said Dr. Ben Bradley, a member of the College of American Pathologists Microbiology Committee.

Measles, once declared eliminated in the United States in 2000 by the Pan American Health Organization, has resurfaced in recent years due to declining vaccination rates. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends that at least 95% of the population be vaccinated to prevent outbreaks. However, many states, including Texas, have fallen below that threshold, leaving communities vulnerable.

NPR health correspondent Maria Godoy highlighted the virus's contagious nature, noting that it is more infectious than COVID-19, smallpox, or Ebola. The National Foundation for Infectious Diseases estimates that an infected individual will spread the disease to 18 others on average.

In Houston, where three unrelated cases have been identified this year, experts are concerned about the virus infiltrating more densely populated areas. "Maybe you say Houston is 90% or 95% [immunized] but there are going to be pockets. There are going to be groups of people there where it is 25%, 30% [immunized]," Dr. Bradley explained. He warned that social events and school activities could facilitate transmission even in passing interactions.

Medical professionals are also cautioning against misinformation circulating online. Some social media posts suggest using vitamin A to prevent measles infection. Dr. Donald Karcher, President of the College of American Pathologists, clarified: "Vitamin A does not diminish the acquiring the infection. It does, apparently in children at least, is proof that it does diminish the mortality of children that have if it's appropriately administered."

Vaccination remains the most effective defense. Two doses of the MMR (measles, mumps, rubella) vaccine are 97% effective in preventing measles infection, according to the CDC. However, infants under one year of age-who are too young to receive the vaccine-and immunocompromised individuals remain at risk.

"If you get vaccinated, you're helping protect those as well who aren't able to get vaccinated," Dr. Karcher emphasized.

The severity of the current outbreak has reignited concerns over vaccine skepticism and misinformation. Robert F. Kennedy Jr., U.S. health secretary, has drawn criticism for promoting alternative treatments unsupported by scientific evidence while launching new government inquiries into the widely debunked theory linking vaccines to autism.

Between 400 to 500 children died annually from measles in the United States prior to the introduction of the vaccine in 1963, CDC data show. Since then, deaths have plummeted, with only a handful of fatalities reported in recent decades-until the two deaths recorded in this outbreak.

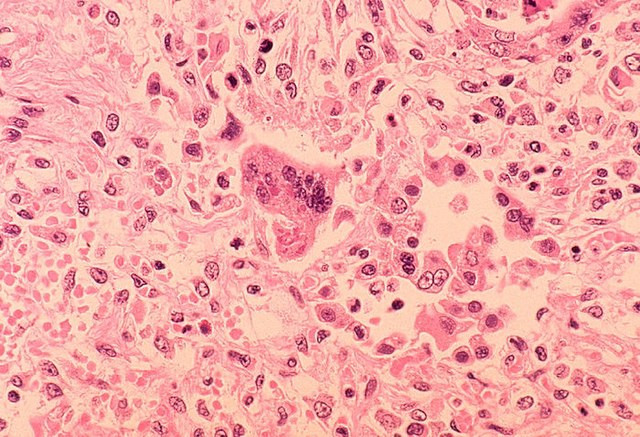

Measles infection can result in severe complications such as pneumonia, encephalitis, and long-term immunological damage. "You hope people don't have to die for others to take this seriously," said Dr. Aaron Milstone, an infectious disease pediatrician at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine.