More than 900 earthquakes have struck Japan's remote Tokara Islands since June 21, the Japan Meteorological Agency (JMA) said Wednesday, marking one of the most intense seismic episodes in the region in recent memory. The unprecedented activity prompted emergency briefings and public anxiety, though no major injuries or structural damage have been reported.

A magnitude 5.5 tremor hit around 3:30 p.m. local time Wednesday, registering a lower 5 on Japan's 7-point seismic intensity scale on Kodakara Island in Kagoshima Prefecture. Earlier that day, a 5.1-magnitude quake struck near Akuseki Island, also reaching a lower 5 on the scale.

"Seismic activity has been very active in the seas around the Tokara island chain since June 21," said Ayataka Ebita, director of the JMA's Earthquake and Tsunami Observation Division. "As of 4 p.m. today, the number has exceeded 900."

Residents across the island chain, which includes seven inhabited islands and houses roughly 700 people, have described sleepless nights and ongoing fear. "It feels like it's always shaking," one resident told regional broadcaster MBC. "It's very scary to even fall asleep."

This level of sustained seismic activity far surpasses a similar episode in September 2023, when the JMA recorded 346 quakes in the same area. The agency has issued advisories urging caution, noting that tremors of comparable strength could occur again.

The surge in earthquakes coincides with new scientific observations off Japan's Pacific coast, where researchers have detected a rare slow-slip earthquake in the Nankai Trough, a key tsunami-generating fault zone. Scientists at the University of Texas Institute for Geophysics, using high-precision borehole sensors installed beneath the seafloor, observed the fault moving gradually over several weeks-an event invisible to land-based instruments.

"It's like a ripple moving across the plate interface," said Josh Edgington, who studied the data during his doctoral research. The event was the third of its kind recorded in the region since 2015 and unfolded roughly 30 miles off Japan's Kii Peninsula.

The Nankai slow-slip episodes are being closely studied for their potential impact on tsunami generation. "This is a place that we know has hosted magnitude 9 earthquakes and can spawn deadly tsunamis," said Demian Saffer, UTIG director and lead author of the study published in Science. The borehole data, he added, provides a "direct view of how the shallow plate boundary behaves between major quakes."

The slow-slip event occurred in areas of unusually high pore-fluid pressure, lending weight to theories that overpressured water may lubricate fault zones, allowing movement without catastrophic rupture. Still, scientists caution that while some energy may be released slowly, locked segments deeper in the fault system remain a concern.

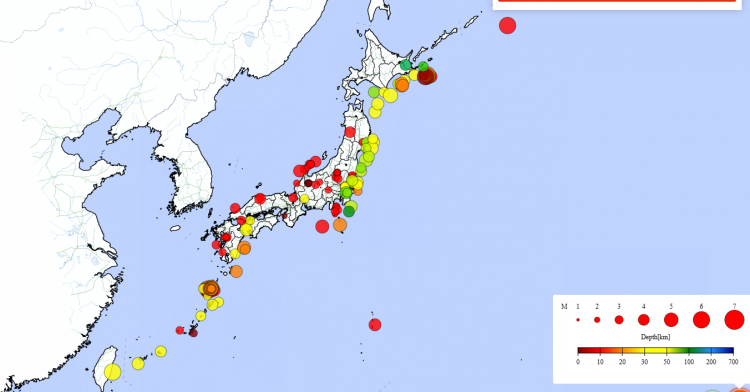

Japan, located at the convergence of four major tectonic plates, experiences about 1,500 seismic events annually and accounts for nearly 18% of the world's earthquakes. On New Year's Day 2024, a magnitude 7.6 quake on the Noto Peninsula killed nearly 600 people, underscoring the persistent threat posed by the nation's geology.