Using data captured by NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter, planetary scientists have discovered that sand dunes on the Red Planet have shown signs of migration.

Focusing on two regions of Mars near the equator, it was found that giant waves of sand known as "megaripples" make stealthy movements from point to point on the surface of the planet. At times, these dunes move so slowly they can easily bypass scientific detection.

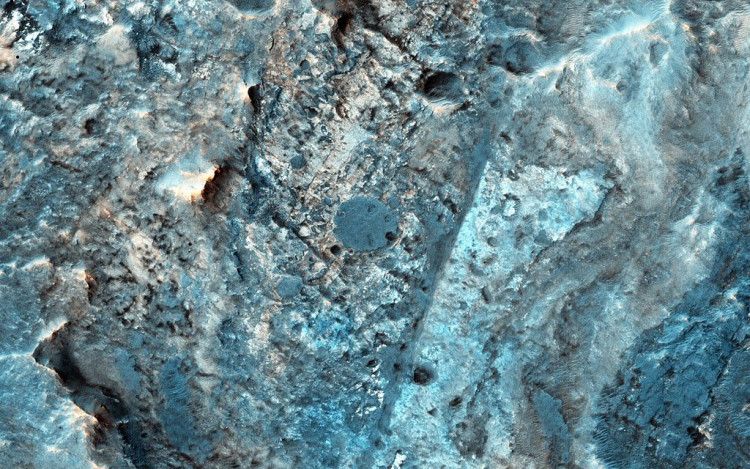

Two sites on Mars were studied, which showed over 1,000 of these megaripples in the McLaughlin crater – one of the Red Planet's interesting craters that formed approximately 4 billion years ago. By comparing images taken eight years apart, the team found evidence of shifting sands, specifically in the Nili Fossae region.

These areas have been found to have multiple signatures of movements in time-lapse images of each site taken years apart. The megaripples, according to the team's estimate, move approximately 10 centimeters each year.

The findings dispel the long-held belief that these megaripples haven't moved since they formed hundreds of thousands of years ago. They are also evidence of stronger-than-expected winds on the Red Planet.

Mars rovers and orbiters have spotted megaripples since the early 2000s on the Red Planet. No change or shift has ever been observed, leading some scientists to think they were relics from ancient Mars when its thicker atmosphere allowed for stronger winds.

The discovery is a surprise to Martian researchers, as decades ago, no evidence has been found of migrating sand dunes. "None of us thought that the winds were strong enough," Jim Zimbelman, planetary geologist at the Smithsonian Institution's Air and Space Museum, told Science.

On Earth, similar slow-moving megaripples also exist, like the mobile sand dunes in the Lut Desert of Iran.

As noted by Zimbelman, the study is proof that there are stronger winds blowing on Mars, which also dispels long-held beliefs. According to the authors, the megaripples are a clear sign of windy weather conditions, which could also cause dust storms.

The Mars Opportunity rover was stuck for several months in what many scientists believe was a storm on the Red Planet. The science team at NASA's JPL suspected that what blanketed the rover's solar panels was airborne dust, which reduced its efficiency to receive or send data for many months.

Gears can also be jammed because of moving sands, an issue that must be considered now when planning for Mars missions, both manned and unmanned, in the future.

Th entire details of the study have been published in the Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets.