With surface temperatures exceeding a maddening 867 degrees Fahrenheit, Venus can easily melt any hardened lander. But the Calypso Venus Scout, a fresh concept, calls for a daring new mission design: a science probe 20 miles below a cloud-borne balloon.

Since Venera 14 in 1982, no lander has reached the Venusian surface. Our only surface data to date come from those few Soviet probes and from the occasional orbiter. Despite Venus being called Earth's twin, we know far too little about it.

We still do not have the technologies to construct a reliable, long-term probe to explore the terrain of Venus as we do on Mars, even after almost 40 years since the last Venera mission. And nobody really wants to spend the money on designing the technology needed for a still-risky Venus operation, given all the excitement in Mars exploration, including potential human visits.

But there might be another way to do it, and as outlined in a white paper recently posted to the preprint site arXiv.org, it's called the Calypso Venus Scout. Right now, Calypso is not under NASA consideration; the author of the paper wrote about it to provide a wider understanding of existing possibilities for the decadal survey, the government's long-term planetary science planning process.

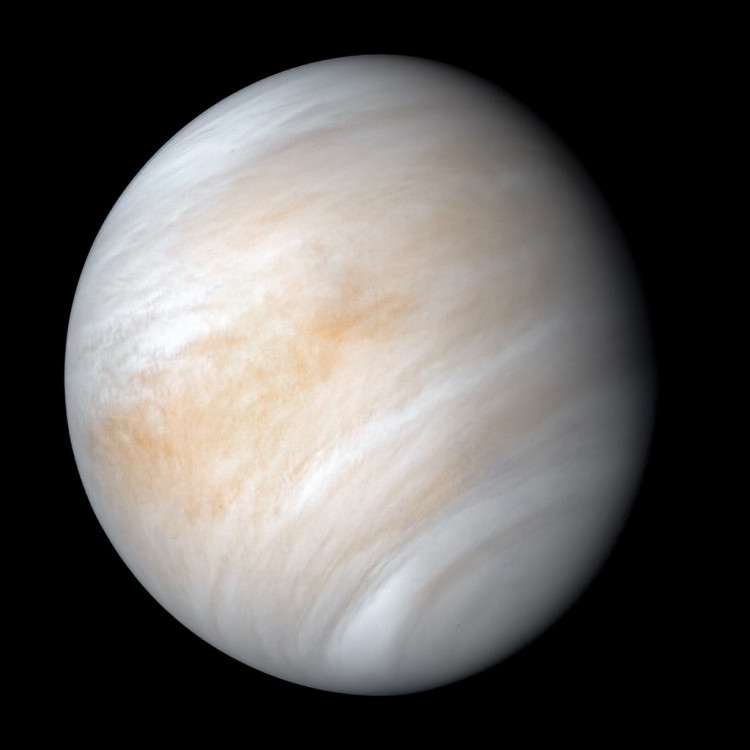

The project seeks to balance Venus' twin challenges: its surface is just too hot, and the mile after mile of dense, hazy cloud layers hamper orbital missions attempting to observe the surface, making accurate measurements extremely challenging.

So Calypso would start right in the middle.

The dense clouds of Venus clear away at an altitude of about 20 miles. Then you should have a clear, unobstructed view of the ground if you can get a probe below that level. And though at that altitude it is still insanely hot, it is not almost as hot as the surface: a comparatively balmy 260 F.

Upon Calypso's arrival at Venus, a large balloon will be deployed in the atmosphere right at the top of the cloud layers, staying steady at an altitude around 30 miles. At that height, no ingenious new technology is needed for the temperature and pressure, and the solar panels will provide the probe with enough power.

The probe will gradually scan Venus' surface in visible and infrared wavelengths on its way up and down to a possible resolution of only a few inches or centimeters. One of Calypso's most effective qualities is that it would not be limited to observing just a single landing spot, but could explore large swaths of the geography of Venus.

Venus is both a time capsule, offering a glimpse of what a planet of Earth-size was up to a long time ago. We will best discover what our own destiny could be by researching Venus further with adventurous missions like Calypso.