A new study suggests that oceans of water may remain buried in Mars' crust rather than being lost to space as previously believed.

Previous studies discovered that Mars was once wet enough to fill the entire surface with an ocean of water 330 to 4,920 feet (100 to 1,500 meters) deep, holding about half as much water as Earth's Atlantic Ocean, according to NASA.

Mars, however, is now cold and dry. Previously, scientists assumed that after the Red Planet's protective magnetic field was lost, solar radiation and the solar wind depleted it of all of its air and water. The volume of water remaining in Mars' atmosphere and ice would only cover a global layer of water 65 to 130 feet (20 to 40 m) thick.

However, new findings suggest that Mars did not lose any of its water to space. Data from NASA's MAVEN (Mars Atmosphere and Volatile EvolutioN) and the European Space Agency's Mars Express orbiter showed that over the course of 4.5 billion years, Mars would have lost a global ocean of water just around 10 to 82 feet (3 to 25 m) deep.

Scientists have found that much of the water Mars once had could still be concealed in the Red Planet's crust, tucked up in the crystal formations of rocks under the Martian surface. They published their findings in the journal Science on March 16 and at the Lunar Planetary Science Conference.

Overall, the researchers, led by Eva Scheller, a planetary scientist at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena, speculated that Mars lost 40% to 95% of its water during the Noachian period, which happened between 4.1 billion and 3.7 billion years ago. Their model proposed that the amount of water on Mars hit its current levels about 3 billion years ago.

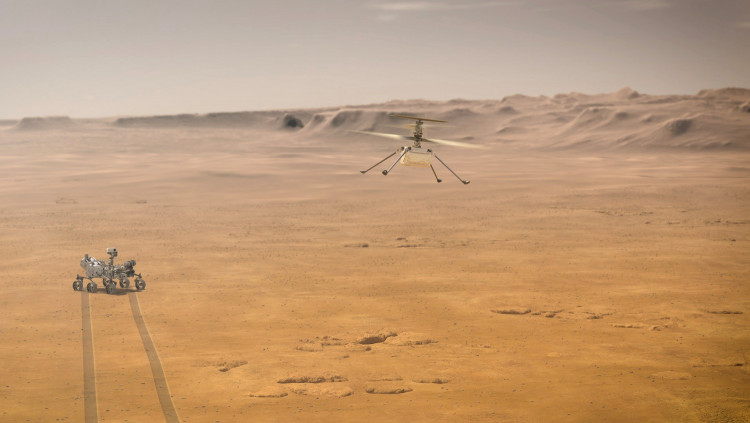

According to Scheller, the latest figures of the amount of water buried in the Martian crust differ greatly due to uncertainties regarding the rate at which Mars lost water to space in the distant past. She went on to suggest that NASA's Perseverance rover, which landed on Mars in February, would assist in the refining of these calculations, "as it is going to one of the most ancient parts of the Martian crust, and so can help us nail down the past process of water loss to the crust much better."

While most of Mars' water could still be tucked away within its crust, future astronauts to the Red Planet may find it difficult to extract that water to support them there, Scheller emphasized.