In a groundbreaking revelation, researchers have discovered that intensive exercise could potentially slow the progression of Parkinson's disease, a neurodegenerative disorder that affects millions worldwide. This discovery could pave the way for new non-pharmacological treatment approaches, emphasizing the importance of physical activity in managing the condition.

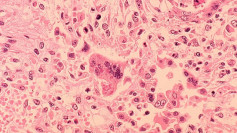

Parkinson's disease is characterized by the loss of dopamine-producing neurons in the substantia nigra, a part of the brain involved in motor control. This loss leads to a range of symptoms, including tremors, impaired balance, loss of motor control, and speech difficulties. However, recent studies have shown that intensive exercise can slow the progression of early-stage Parkinson's disease.

A team of neuroscientists from the Faculty of Medicine of the Catholic University, Rome Campus, and the A. Gemelli IRCCS Polyclinic Foundation, in collaboration with multiple research institutes, conducted a study to understand the biological mechanisms behind the positive effects of exercise on Parkinson's disease. The study, published in the journal Science Advances, found that intensive exercise could decelerate the progression of Parkinson's disease by influencing brain plasticity.

The research team used a four-week treadmill training protocol on rats with symptoms of Parkinson's disease. They found that regular exercise prevented the degradation of neurons vital for movement. The active rats had twice as many dopamine-producing neurons in the substantia nigra as the sedentary rats, indicating that exercise may protect these cells from the harmful effects of abnormal proteins associated with Parkinson's disease.

Moreover, the researchers discovered that neurons in the active rats maintained the ability to strengthen connections with other cells, a trait critical for relaying motor signals. This characteristic was impaired in sedentary rats. The researchers believe this may be because exercise increased levels of certain proteins in the animals' brains, such as brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), which helps neurons survive and grow.

The study also found that intensive physical activity reduced the spread of pathological alpha-synuclein aggregates, a key contributor to the neuron dysfunction seen in Parkinson's disease. This neuroprotective effect of physical activity was associated with the survival of neurons releasing the neurotransmitter dopamine and with the consequent striatal neurons' ability to express a form of dopamine-dependent plasticity, aspects otherwise impaired by the disease.

These findings suggest that regular exercise may be a way of curbing the progression of Parkinson's disease. The work could also lead to the development of new drugs for the disease. "Once you know the molecular pathways that are being induced by exercise, you could conceive of having drugs that simulate those effects," says David Eidelberg at the Feinstein Institutes for Medical Research in New York.

While the research offers promising insights, it's important to note that it may not directly translate to humans, especially as it only looked at one aspect of Parkinson's disease pathology - the abnormal protein strands. Nonetheless, the study underscores the potential of exercise as a non-pharmacological intervention in the early stages of Parkinson's disease, opening new avenues for treatment and management of this debilitating condition.