Researchers have discovered a potential connection between accelerated biological aging and the increasing incidence of certain types of cancer in younger adults. The findings, presented at the American Association of Cancer Research's annual conference in San Diego, suggest that interventions to slow down biological aging could be a new avenue for cancer prevention.

Dr. Yin Cao, an associate professor of surgery at the Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis and senior author of the study, emphasized the importance of understanding the factors driving the rise in early-onset cancers. "We all know cancer is an aging disease. However, it is really coming to a younger population. So whether we can use the well-developed concept of biological aging to apply that to the younger generation is a really untouched area," she said.

The research team, led by graduate student Ruiyi Tian, analyzed the medical records of 148,724 people aged 37 to 54 from the UK Biobank. They focused on nine blood-based markers that correlate with biological age, including albumin, creatinine, glucose, c-reactive protein, lymphocyte percent, mean cell volume, red cell distribution width, alkaline phosphatase, and white blood cell counts. Using an algorithm called PhenoAge, the researchers calculated each person's biological age and compared it to their chronological age to determine accelerated aging.

The study found that people born in 1965 or later were 17% more likely to show accelerated aging compared to those born between 1950 and 1954. After adjusting for potential biases, the researchers discovered that accelerated aging was associated with an increased risk of early-onset cancers, particularly lung, stomach and intestinal, and uterine cancers.

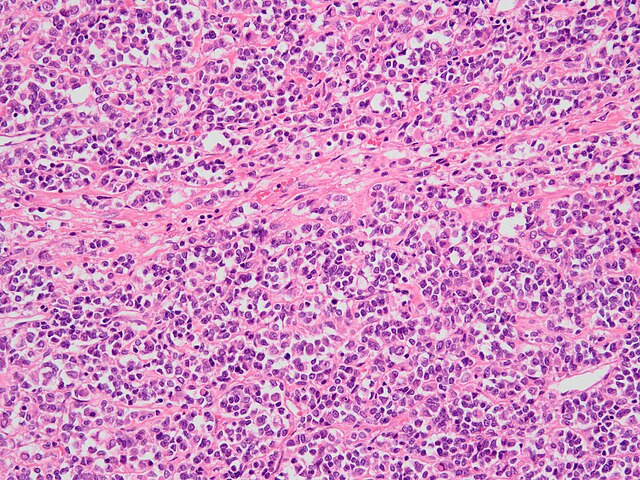

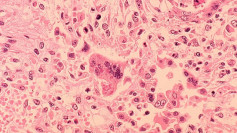

Compared to individuals with the least amount of faster aging, those who scored highest had twice the risk of early-onset lung cancer, more than 60% higher risk of gastrointestinal tumors, and more than 80% higher risk of uterine cancer. While the study wasn't designed to answer why these specific cancer types had the strongest ties to accelerated aging, Tian offered some theories, such as the lungs' limited ability to regenerate and the link between inflammation and stomach and intestinal cancers.

Dr. Anne Blaes, a professor and director of the Division of Hematology and Oncology at the University of Minnesota medical school, who was not involved in the research, praised the study's potential to identify people at higher risk of getting cancer at a young age. "We're seeing more and more cancers, especially GI cancers and breast cancers, in younger individuals. And if we had a way of identifying who's at higher risk for those, then really, you can imagine we'd be recommending screening at a different time," she said.

Blaes also noted that if individuals with faster cellular aging can be identified, targeted lifestyle interventions like nutrition, exercise, and sleep could be implemented. Additionally, medications called senolytics, which are thought to target and eliminate damaged and aging cells, are being tested in cancer survivors who often show greater biological aging.

While the study's findings are exciting, Cao acknowledged its limitations, such as the lack of long-term follow-up and the need to test the association in more diverse populations. Blaes agreed, stating, "It's super interesting. It's not quite prime time, where we would go out and prescribe those medications for people, but this is really, really important work."

As research continues to unravel the complex relationship between accelerated aging and early-onset cancers, the hope is that this knowledge will lead to better prevention strategies and earlier detection of cancers in younger individuals. By understanding the factors contributing to accelerated aging and developing targeted interventions, healthcare professionals may be able to reduce the burden of cancer in future generations.