A damning report released by the Infected Blood Inquiry has exposed the United Kingdom's worst treatment disaster, revealing that British authorities and the National Health Service (NHS) knowingly exposed tens of thousands of patients to deadly infections through contaminated blood and blood products. The scandal, which occurred between the 1970s and early 1990s, is believed to have caused the deaths of an estimated 3,000 people, leaving many others with lifelong illnesses.

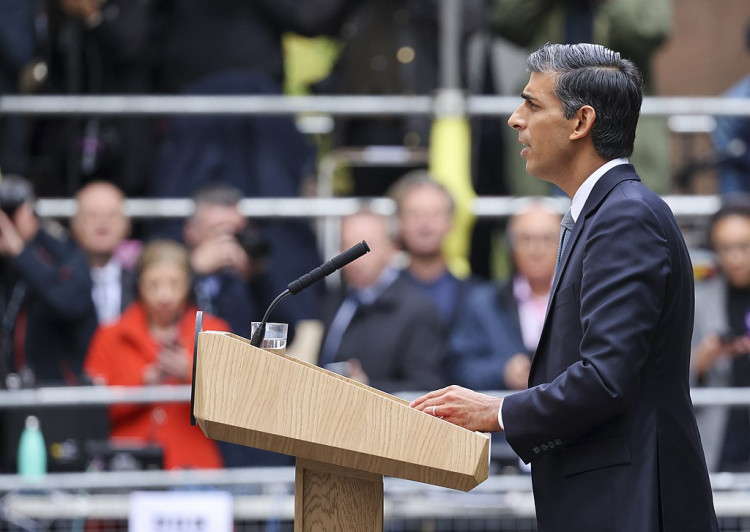

In response to the report's findings, Prime Minister Rishi Sunak apologized to the victims and promised to pay "comprehensive compensation" to those affected by the scandal. "Whatever it costs to deliver this scheme, we will pay it," Sunak told the House of Commons on Monday, describing the release of the report as a "day of shame for the British state." The government is expected to set out the details of the compensation package, reportedly earmarked at around £10 billion ($12.7 billion), on Tuesday.

The 2,527-page report, authored by former judge Brian Langstaff who chaired the inquiry, found that the infected blood scandal "could largely have been avoided" and that there had been a cover-up to hide the truth. Langstaff slammed successive governments and medical professionals for "a catalogue of failures" and refusal to admit responsibility, stating that "deliberate attempts were made to conceal the scandal, and there was evidence of government officials destroying documents."

The inquiry revealed that around 1,250 people with bleeding disorders, including 380 children, were infected with HIV-tainted blood products, with three-quarters of them having since died. Up to 5,000 others who received the blood products developed chronic hepatitis C, while an estimated 26,800 others were infected with hepatitis C after receiving blood transfusions, often given in hospitals after childbirth, surgery, or an accident.

Langstaff emphasized that many of the deaths and illnesses could have been avoided had the government taken steps to address the risks linked to blood transfusions or the use of blood products, noting that since the 1940s and early 1980s, it had been known that hepatitis and the cause of AIDS, respectively, could be transmitted this way. Unlike many other developed countries, officials in the U.K. failed to ensure rigorous blood donor selection and screening of blood products.

The report also highlighted the compounding of the victims' agony by authorities refusing to accept responsibility, falsely telling patients they had received the best treatment available, and delaying informing them about their infections. Langstaff described the collective failures as "a calamity."

Campaigners who have fought for decades to bring official failings to light and secure government compensation welcomed the report's findings. Andy Evans, of campaign group Tainted Blood, said, "We have been gaslit for generations. This report today brings an end to that. It looks to the future as well and says this cannot continue."

Opposition Labour party leader Sir Keir Starmer apologized for his party's involvement while in government and welcomed the prime minister's confirmation of financial support for victims, pledging to work with him to ensure swift implementation.

The government has already made interim pay-outs of £100,000 each to about 4,000 survivors and bereaved partners, with further interim payments potentially being announced on Tuesday before the full compensation scheme is implemented. The two main groups affected by the scandal were people with haemophilia or similar rare genetic disorders preventing their blood from properly clotting, and those who had received blood transfusions after childbirth, accidents, or during medical treatment.