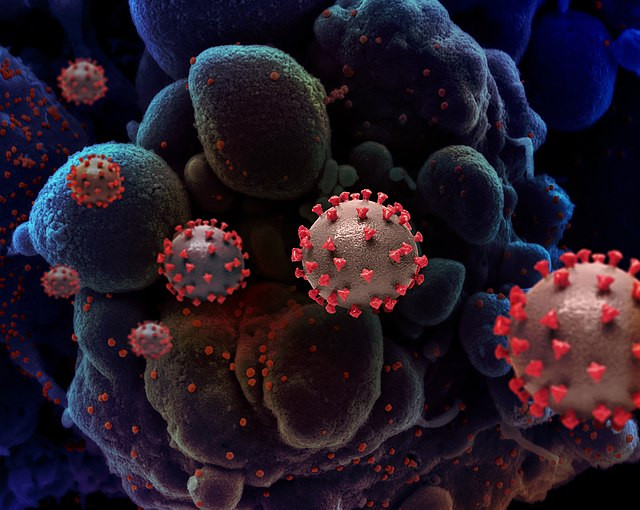

Researchers at Northwestern Medicine Canning Thoracic Institute have uncovered a startling connection between COVID-19 infections and cancer regression, raising the possibility of using the virus's impact to develop new cancer treatments. The study, published in the Journal of Clinical Investigation, reveals that the RNA from the SARS-CoV-2 virus can activate specific immune cells capable of attacking cancer, offering a potential new avenue for patients with advanced cancers resistant to existing therapies.

"This discovery opens up a new avenue for cancer treatment," said Dr. Ankit Bharat, senior author and chief of thoracic surgery at the Canning Thoracic Institute. "We found that the same cells activated by severe COVID-19 could be induced with a drug to fight cancer, and we specifically saw a response with melanoma, lung, breast, and colon cancer."

The study focuses on "inducible nonclassical monocytes" (I-NCMs), a rare type of immune cell that multiplies in response to inflammation, such as that seen during severe COVID-19 infections. Unlike typical immune cells, which patrol blood vessels for threats but often cannot penetrate tumors, I-NCMs retain a unique receptor, allowing them to infiltrate tumor sites and trigger an aggressive immune response.

"Once inside the tumor environment, these cells release chemicals that recruit the body's natural killer cells," Bharat explained. "These killer cells swarm the tumor and start attacking cancer cells directly, helping to shrink the tumor."

While the initial findings are promising, Dr. Bharat emphasized that more research is needed before these insights can be translated into clinical practice. The current research primarily involved animal models and human tissue samples, but researchers are optimistic about future clinical trials. "Our next steps will involve clinical trials to see if we can safely and effectively use these findings to help cancer patients," he noted.

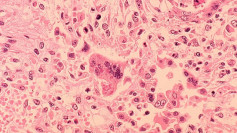

In preliminary tests, a compound that mimics the effect of COVID-19 RNA reduced tumors by up to 70% in mice with human cancers. Researchers believe this approach could be particularly beneficial for patients with stage 4 cancers who have exhausted other treatment options.

The study builds on related observations, including a case documented in the British Journal of Haematology. In that instance, a man diagnosed with terminal stage III lymphoma experienced significant tumor regression after contracting COVID-19. Within months of recovering from the respiratory illness, his tumors disappeared, highlighting the potential link between immune system activation during infection and cancer response.

However, Bharat cautioned that these findings do not suggest that COVID-19 is a reliable or safe method for treating cancer. Instead, scientists aim to harness the immune pathways activated by the virus through controlled therapies. "We are in the early stages, but the potential to transform cancer treatment is there," Bharat said.

The implications of this research could be far-reaching. By targeting the immune response pathway activated during severe COVID-19 infections, scientists hope to replicate the effects without exposing patients to the risks of the virus. "By manipulating that pathway through a drug, we might be able to help patients with many different types of cancers," Bharat stated.

As the study progresses, the medical community remains cautiously optimistic. Cancer remains one of the leading causes of death worldwide, and new treatment strategies are urgently needed. According to the American Cancer Society, an estimated 611,720 people will die from cancer in the U.S. this year, with lung cancer accounting for the majority of these deaths.