Beijing's sweeping export restrictions on rare earth elements and magnets are reverberating through the global economy, disrupting production lines from Munich to Detroit and sparking urgent diplomatic engagement. The curbs, imposed in April, have halted shipments of critical minerals used in electric vehicles, aerospace systems, semiconductors, and military hardware, and have led to suspension of output at multiple European auto parts plants.

Germany's BMW confirmed Wednesday that part of its supplier network has been affected by the shortages, though its own plants remain operational. The European Association of Automotive Suppliers, CLEPA, warned that several production lines across the continent have already been shut down. "If the situation is not changed quickly, production delays and even production outages can no longer be ruled out," Hildegard Mueller, head of Germany's auto lobby, told Reuters.

The crisis highlights China's dominance in the critical minerals sector-producing roughly 90% of the world's rare earths-and its leverage in an escalating trade war with the United States. The move also coincides with retaliatory actions taken by Beijing in response to steep tariffs imposed by President Donald Trump, some as high as 145%, before being scaled back following a market selloff.

"Our administration officials continue to be engaged in correspondence with their Chinese counterparts," White House spokeswoman Karoline Leavitt said Tuesday. "I can assure you that the administration is actively monitoring China's compliance with the Geneva trade agreement."

The Chinese curbs are hitting a broad swath of industries. Magnets made from rare earth alloys are used in products ranging from vehicle motors and sensors to defense systems and robotics. Shipments remain stalled at ports across China, as manufacturers await export license approvals that are trickling out at an uneven pace. CLEPA noted that only about a quarter of applications submitted since April have been approved, with some rejected on "highly procedural grounds."

"Procedures seem to vary from province to province and in several instances IP-sensitive information has been requested," CLEPA added. Without a streamlined process, the group warned, more production facilities could run out of stock within weeks.

The Alliance for Automotive Innovation, which represents major manufacturers including General Motors, Toyota, Volkswagen, and Hyundai, issued a letter to the Trump administration in May warning: "Without reliable access to these elements and magnets, automotive suppliers will be unable to produce critical automotive components, including automatic transmissions, throttle bodies, alternators, various motors, sensors, seat belts, speakers, lights, motors, power steering, and cameras."

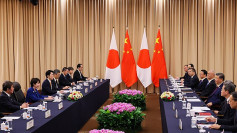

India's Bajaj Auto has also raised concerns, warning that delays in securing rare earth magnets could "seriously impact" electric vehicle output. A delegation of Indian auto executives is expected to travel to China in the coming weeks to seek relief. Japanese and European officials are also pressing for urgent talks with Beijing's Ministry of Commerce.

While some companies like BMW and Volkswagen are experimenting with magnet-free electric motor designs to reduce reliance on China, the effort remains limited in scope. BMW said it still requires rare earths for auxiliary motors powering features like windshield wipers and window rollers.

Frank Fannon, former U.S. assistant secretary of state for energy resources, said the disruptions underscore systemic vulnerabilities. "We have a production challenge (in the U.S.) and we need to leverage our whole of government approach to secure resources and ramp up domestic capability as soon as possible. The time horizon to do this was yesterday," Fannon stated.

On Wednesday, President Trump wrote on social media that Chinese President Xi Jinping is "VERY TOUGH, AND EXTREMELY HARD TO MAKE A DEAL WITH," reinforcing tensions ahead of their expected call this week to address the export curbs.