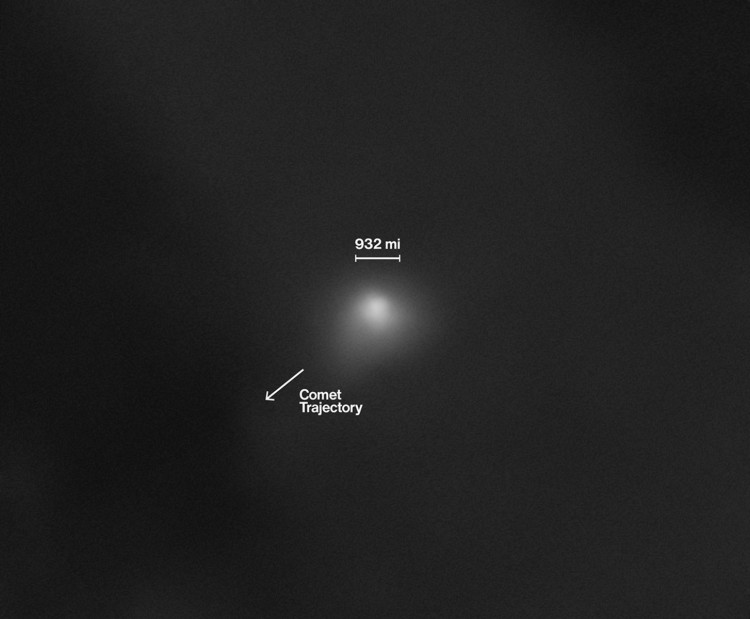

An interstellar object moving at roughly 137,000 miles an hour is making its closest approach to Earth this week, drawing intense scrutiny from astronomers and planetary-defense officials despite posing no direct threat. Known as 3I/ATLAS, the comet is only the third confirmed visitor from beyond the solar system and is traveling on a hyperbolic trajectory that has sharpened concerns about how quickly such objects can be detected and tracked.

On Friday, 3I/ATLAS will pass within about 167 million miles of Earth, closer than Mars is currently positioned. Scientists say the proximity offers a rare observational opportunity while also serving as a real-world stress test for global monitoring systems designed largely around slower, solar-bound asteroids.

The comet was discovered last July by the ATLAS survey, and its speed immediately set it apart. When first observed, it was already moving fast enough to confirm it was not gravitationally bound to the Sun, meaning it arrived from interstellar space with little advance warning and will exit the solar system permanently.

Researchers emphasize that the object is not on a collision course. Still, its velocity has forced agencies such as NASA and the United Nations-backed International Asteroid Warning Network to treat the flyby as a high-priority tracking exercise.

Chemically, the object has raised additional interest. NASA astrochemists have detected what they described as substantial outgassing of hydrogen cyanide and carbon dioxide, levels significantly higher than those typically observed in comets originating within the solar system. Scientists say the data could provide insight into how planetary systems beyond the Sun form and evolve.

The trajectory has also prompted debate. Harvard astrophysicist Avi Loeb has noted that the comet's path is "statistically unlikely," citing its close alignment with the solar system's ecliptic plane. While Loeb has stressed that such anomalies do not imply artificial origin, he has argued they warrant careful analysis given how little is known about interstellar objects.

Observational challenges remain severe. Astronomer David Jewitt, who has studied 3I/ATLAS using the Hubble Space Telescope, told NASA earlier this year, "It's like glimpsing a rifle bullet for a thousandth of a second." He said the extreme velocity makes it nearly impossible to trace the object back to a specific star system.

The flyby has highlighted structural limits in current planetary-defense planning. Most near-Earth monitoring systems are optimized for objects moving far more slowly, often allowing years of warning time. By contrast, scientists estimate that if 3I/ATLAS had been on a collision trajectory, Earth might have had less than six months to respond.

Key figures underscore the challenge:

- Speed: ~137,000 mph (about 40 miles per second)

- Distance at closest approach: ~167 million miles

- Known interstellar visitors: Only three to date

Astronomers worldwide are using the encounter to gather as much data as possible before the comet fades from view. For the public, the object may appear as a faint, star-like point through binoculars or small telescopes, with livestreams offered by observatories including the Virtual Telescope Project.