A big splash in the news was made by the blockbuster announcement of discovering phosphine in the clouds of Venus. But pushback started to emerge even as specifics of the findings came to light.

Scientists have had some time in the days since to express their arguments, which fall into two major camps. On the one hand, there are those who doubt the identification itself and whether what they claim to have seen was certainly seen by the team. And the meaning is strongly scrutinized by a second attack and whether life is a good conclusion to arrive at or not.

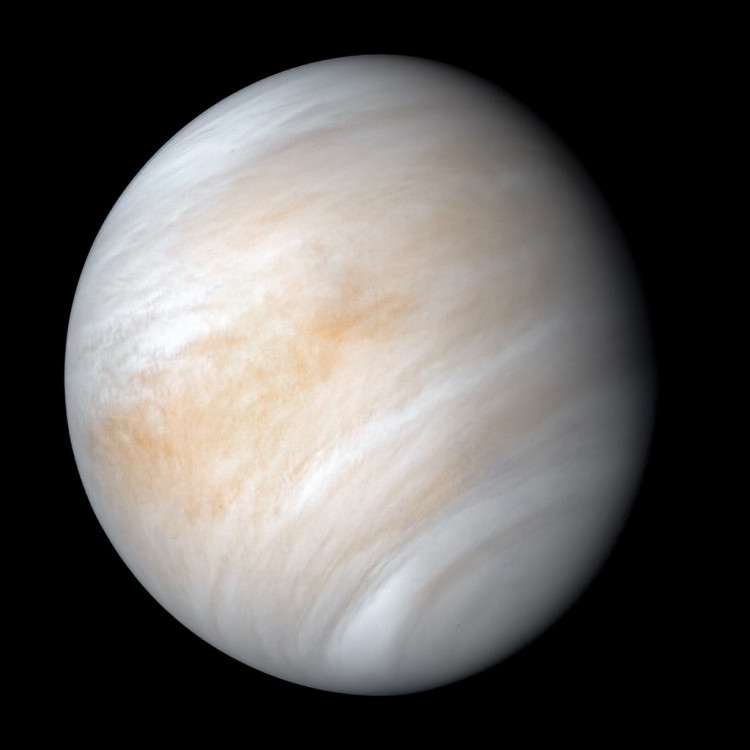

And those who are cynical think the findings are interesting. Venus has a hot and hellish surface, but for a long time, there has been the possibility that life could occur in its comparatively balmy upper atmosphere. Everyone knows that this is not the last word on the matter, which is likely to take years to figure out entirely.

"Obviously if it's correct, it's an extremely cool result and potentially has profound implications," John Carpenter, an observatory scientist at the Atacama Large Millimetre/submillimetre Array (ALMA) in Chile, said in an interview. "But grand claims demand grand evidence."

The molecule phosphine, or PH3, which is made from one atom of phosphorus bound to three atoms of hydrogen, is at the core of this debate. For many species, including humans, phosphine is a nasty and toxic gas, but it is created by bacteria living in decaying waste and swamps where oxygen is scarce, as well as in some animals' intestines.

Using the James Clerk Maxwell Telescope and ALMA, astronomers searched for telltale dips in the light of Venus that would suggest the presence of various chemicals and found a phosphine-associated one. The outcome is especially perplexing since the atmosphere of Venus is full of carbon dioxide and other molecules containing oxygen that should tear phosphine apart in no time. It is bewildering to have it present in some quantity.

But did the test team see phosphine for real? The results involve a fair amount of noise, which could simply be mimicking a phosphine signal, Carpenter suggested.

Michael Way, a physical scientist at New York City's NASA Goddard Center for Space Studies, approved.

Way pointed out that there is a sulfur dioxide-associated signature, SO2, at almost the same light frequency. The third most abundant gas in the atmosphere of Venus is sulfur dioxide, so its existence might account for the discovery of phosphine.

In order to check their findings, the team that made the original phosphine finding is interested in doing follow-up observations. And independent investigators are both preparing their own phosphine searches with the NASA Stratospheric Observatory for Infrared Astronomy (SOFIA) telescope, the Very Large Telescope in Chile, and the European Space Agency's BepiColombo spacecraft, which will soon travel past Venus on its way to Mercury.