Besides Earth, Jupiter may be the first planet known to host displays of atmospheric light called "sprites" or "elves."

Sprites and elves are two kinds of atmospheric lights that appear as lightning shifts the electromagnetic state above a storm in the atmosphere. These electromagnetic upsets on Earth allow nitrogen molecules to give off a brief, reddish glow in the upper atmosphere.

Named from European mythology for mischievous fairy-like beings, sprites are transient luminous events (TLE) seen from well above a lightning storm, including Earth storms. These TLEs, which brighten miles of heavens above a thunderstorm and closely resemble a jellyfish, are caused by lightning. Each sprite lasts only a few milliseconds, which makes it hard to spot them.

Elves, though, aren't named after the mythological creature. According to NASA, ELVES is an acronym that stands for Emission of Light and Very Low Frequency perturbations due to Electromagnetic Pulse Sources. Elves are caused by lightning and occur high above the clouds, like sprites. Their form is what sets them apart. Elves in the upper atmosphere appear like a flattened disk glowing. Though they also appear for only a few milliseconds, elves will grow bigger than sprites. We see them grow up to 200 miles across on Earth.

Scientists have hypothesized that on other planets that crackle with lightning, certain atmospheric phenomena can occur. Yet no one had ever seen signs of sprites or elves on another planet until now.

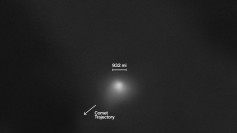

The ultraviolet spectrograph on NASA's Juno spacecraft, in orbit around Jupiter, captured 11 super-rapid light bursts around the giant planet from 2016 to 2020. Those flashes, published online in the Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets on Oct .27, lasted 1.4 milliseconds on average, which is just as brief as the Earth's sprites and elves. The ultraviolet light was the kind of glow predicted from sprites or elves on Jupiter, whose atmosphere is mainly composed of hydrogen, rather than nitrogen, at wavelengths produced by molecular hydrogen.

In order to prove that they are really sprites or elves, Juno will need to detect a lightning bolt at the same position as one of these bright flares, says study coauthor Rohini Giles, a planetary scientist at the Southwest Research Institute in San Antonio, Texas.

"But there is reasonably good circumstantial evidence," Giles said in a NASA statement. A few hundred kilometers above Jupiter's layer of water clouds, where lightning normally forms, the flashes originated, and some erupted in known stormy areas.

Observations of these events when Juno is closer to Jupiter can reveal their scale and help decide if the atmosphere of Jupiter is illuminated by sprites or elves (or both).