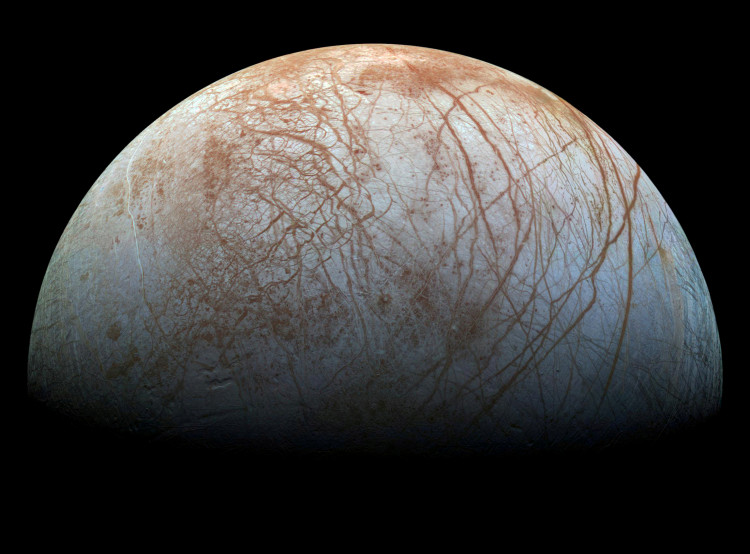

On Jupiter's icy moon Europa, strong eruptions spew into space, raising questions among eager scientists on Earth: What would blast out from mile-high plumes? And is it possible to find evidence of life on these plumes?

Instead of coming from deep inside the oceans of Europa, according to recent evidence from researchers at Stanford University, the University of Arizona, the University of Texas, and NASA, some eruptions may originate from water pockets embedded in the ice shell itself.

The researchers created a model using images captured by the Galileo spacecraft, showing how a combination of freezing and pressurization could result in a cryo-volcanic eruption or a water eruption. The observations published in Geophysical Research Letters on Nov. 10 have an impact on Europa's underlying sea habitability and can explain eruptions of other ice bodies in the solar system.

Scientists have hypothesized that the vast ocean concealed beneath the ice crust of Europa could contain the elements needed to sustain life. But short of sending the moon a submersible to investigate, it's impossible to know for sure. That's one reason why the plumes of Europa have drawn so much interest: if the eruptions originate from the subsurface ocean, a spacecraft like the one proposed for NASA's forthcoming Europa Clipper mission might more quickly detect the elements.

The researchers based their study on Manannán, an 18-mile-wide crater on Europa that was formed some tens of millions of years ago by a collision with another celestial object. Reasoning that such a collision would have produced a large amount of heat, they modeled how it may have caused the water to explode by melting and eventually freezing a water pocket inside the ice hull.

"Understanding where these water plumes are coming from is very important for knowing whether future Europa explorers could have a chance to actually detect life from space without probing Europa's ocean," said lead author Gregor Steinbrügge.

The research also offers projections of how saline the frozen surface and ocean of Europa can be, which in turn could impact the clarity of the radar waves of its ice shell. The estimates, based on Galileo's imaging from 1995 to 1997, indicate that the ocean of Europa can be around one-fifth as salty as the ocean of Earth, a consideration that will boost the ability of the radar sounder of the Europa Clipper mission to gather data from its interior.

The results may deter astrobiologists from hoping that the erupting plumes of Europa might provide clues about the ability of the internal ocean to sustain life, given the implication that plumes may not have to attach to the ocean of Europa. The new model, however, gives insights into untangling the dynamic surface features of Europa, which are subject to hydrological cycles, the pull of the gravity of Jupiter, and the unseen tectonic forces within the icy moon.