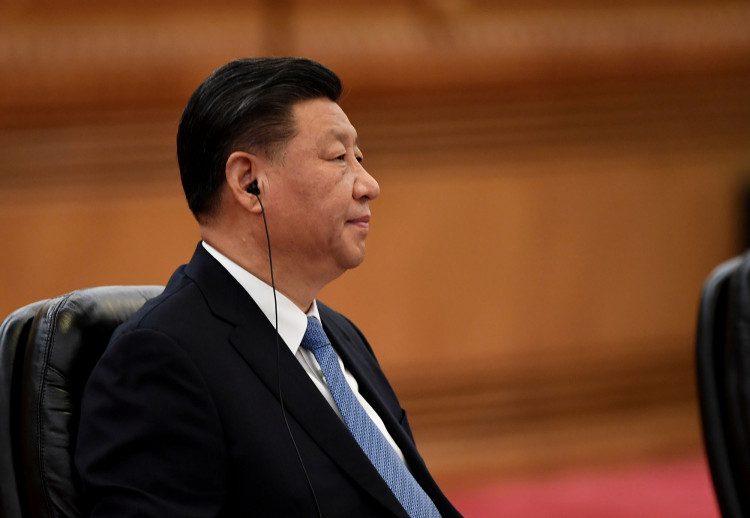

Chinese President Xi Jinping's relentless anti-corruption campaign, ongoing for a decade, has now intensified its focus on the finance industry, revealing the depth of the Chinese leader's commitment to purging corruption from the Communist Party and state institutions. The campaign, which has already seen the punishment of at least 4.7 million officials according to a 2022 report by Global Times, shows no signs of abating and is deeply impacting critical sectors of the Chinese economy.

In 2023, the number of investigations into senior officials increased by 40% compared to the previous year, as reported by South China Morning Post. This surge in scrutiny coincides with economic challenges like the property crisis and high local government debt. Alex Payette, CEO of Cercius Group, a consultancy specializing in Chinese politics, observes that Xi's approach prioritizes ideological control over economic stability, a move that aligns with the party's longer-term goals of maintaining power.

"Xi simply does not see economic stability as the prime concern, despite the fact that the party extensively relies on growth and development to control grievances and generate support," Payette stated. He also highlighted Xi's strategy to insulate the economy from foreign sanctions and place it firmly under party control.

Victor Shih, an associate professor at the University of California, San Diego, explained Xi's rationale: "He would like officials to behave in a clean and efficient way all the time [but] has reduced official pay and benefits to the majority of officials," which paradoxically may increase the temptation for corruption.

Recent targets of the campaign include high-ranking officials in state-owned banks and regulatory bodies, as well as the oil and tobacco sectors. Andrew Wedeman, a professor at Georgia State University, noted a shift in focus from elite bureaucrats to mid-level 'grey suits', signaling a move away from factional purges to broader systemic clean-up efforts.

Xi's crackdown has not been without controversy, with critics suggesting it also serves as a tool for eliminating political rivals. The arrest of Tang Shuangning, former chairman of the state-owned banking giant Everbright, and the public confession of former national football coach Li Tie, who admitted to match-fixing and bribery, have underscored the campaign's intensity.

This sustained anti-corruption effort, unparalleled in its duration and reach, reflects the complexities of modern Chinese society compared to the Mao era. Vivienne Shue, professor emeritus at Oxford University, sees it as a "staged and targeted approach" necessary given the stratification of Chinese society and economy.

The campaign's persistence, amplified by state media's detailed coverage of high-profile cases, resonates with public sentiment against corruption. Yet, as Wedeman observes, it resembles "the American war in Vietnam - the body count keeps rising but we never get any closer to the light at the end of the tunnel."

As Xi Jinping's rule continues, so too does his unwavering crackdown on corruption. The campaign, while bolstering his power within the party, also highlights the challenges of governing a rapidly evolving and complex nation like China.