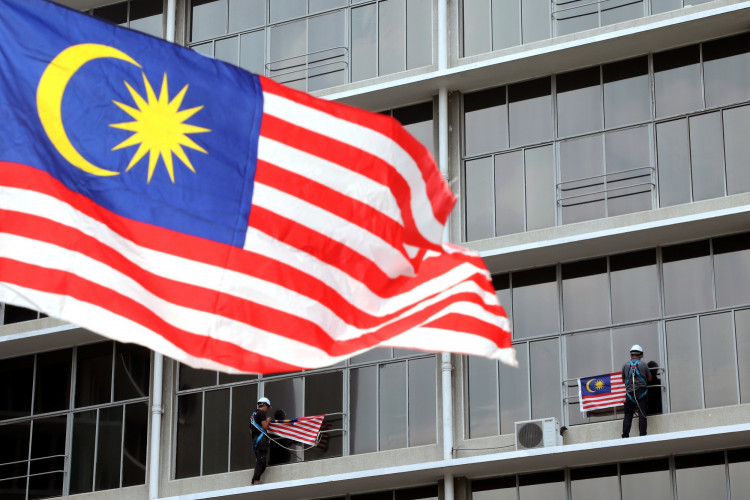

As the United States and China wage a fierce battle for supremacy in the global semiconductor industry, Malaysia has emerged as an unexpected beneficiary, attracting billions of dollars in foreign investment and solidifying its position as a key player in the global chip supply chain.

The ongoing Chip War between the two superpowers has prompted many semiconductor manufacturers to seek alternatives to China, with Malaysia's Penang state becoming a prime destination, as reported by Financial Times. The influx of foreign companies, including industry giants like Intel, Micron, and Infineon, has led to a surge in investment, with Penang attracting RM60.1bn ($12.8bn) in foreign direct investment in 2023 alone, surpassing the total it received from 2013 to 2020 combined.

"It's a rush. It's not only Chinese companies [setting up in Penang]. It's Korean, it's Japanese, and it is western," says Marcel Wismer, CEO of Malaysian contract manufacturer Kemikon. "And all of this is related to the tech war between the US and China."

The US restrictions on Chinese technology, particularly in the chipmaking sector, have driven this shift, as companies seek to protect themselves from geopolitical disruptions and maintain access to advanced manufacturing capabilities. Chinese companies, facing pressure from their Western clients, are also moving or expanding to Malaysia to avoid losing business.

Malaysia's Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim considers the development of the country's semiconductor industry and workforce into higher-value manufacturing a "critical goal." In an interview with the Financial Times, he acknowledged that Malaysia is at "a very critical moment, a departure from our history," while expressing pride in Penang's boom.

However, the rapid growth has also exposed some vulnerabilities in Malaysia's semiconductor ecosystem. The country faces a severe talent shortage, with the electrical and electronics sector alone requiring 50,000 engineers, while only 5,000 engineering students graduate each year. Additionally, Malaysia has yet to create a domestic semiconductor champion that can drive further growth and investment.

Despite these challenges, Malaysia's position in the global semiconductor supply chain remains strong. The country is already the world's sixth-largest semiconductor exporter and holds 13 percent of the global semiconductor packaging, assembly, and testing market. It is also the origin for 20 percent of US semiconductor imports annually, surpassing Taiwan, Japan, and South Korea.

The investment rush has caught even Penang's business-friendly government by surprise, with industrial land prices soaring and traffic jams becoming a regular feature. The state government has had to become more selective in allocating land to incoming companies due to the growing demand.

As Malaysia aims to move up the semiconductor value chain, attracting front-end fabrication plants, known as fabs, has become a top priority. Zafrul Aziz, Malaysia's minister for investment, trade, and industry, expresses optimism about the country's prospects, stating, "I am optimistic that we will attract more than one [fab]. All it takes is one to kick-start a wave."

The rise of Chinese companies in Penang has also raised concerns about potential US scrutiny, as Washington continues to tighten restrictions on Chinese technology. Some analysts and industry groups fear that the US may restrict products and equipment built in Malaysia by the growing number of Chinese companies.

Despite these uncertainties, Malaysia's semiconductor industry remains poised for growth, with global companies increasingly viewing the country as a key component of their supply chain diversification strategies. As Gautam Puntambekar, country executive for Bank of America, notes, "When you talk about semiconductors, Malaysia is invariably part of the conversation."