U.S. health-care costs are poised for their sharpest increase in more than a decade, with medical inflation driving up prices for patients, employers and insurers ahead of 2026. Medical care costs rose 4.2% in August, outpacing the overall inflation rate of 2.9%, according to the Labor Department's Consumer Price Index. Hospital and outpatient services jumped 5.3%, while doctor visits climbed 3.5%, signaling broad-based price pressure.

Employer-sponsored health insurance, which covers about 154 million Americans, is expected to see average cost increases of nearly 9% per worker in 2026, according to surveys by Mercer and the Business Group on Health. That would mark the largest annual jump since 2010. Many employers say they can no longer absorb the rising costs without passing some of them along to employees through higher premiums, deductibles and copays.

"It's almost a perfect storm that's hitting employers right now," said Larry Levitt, executive vice president for health policy at KFF. "The price of health care is going up faster than it has in a long time, and typically when an employer is getting a big increase from an insurer, the employer is turning around and trying to pass on some or all of that to its workers."

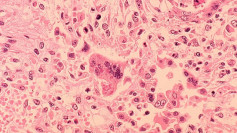

Prescription drug prices are a key driver of the surge, particularly cancer treatments and expensive GLP-1 weight-loss and diabetes medications such as Novo Nordisk's Wegovy and Eli Lilly's Zepbound. Employers surveyed by BGH project a 12% increase in pharmacy costs next year, following an 11% increase this year. "Cancers have been for the fourth year in a row, the top condition driving healthcare costs - cancers at younger ages, later stage diagnoses," said Ellen Kelsay, BGH president and CEO. She called obesity medications "a close second" in driving cost growth.

Nearly two-thirds of large employers offer access to GLP-1s, compared with less than half of small employers, according to Mercer. With demand growing, some companies are tightening eligibility rules or exploring cheaper alternatives, including allowing employees to purchase lower-cost compounded versions through health savings accounts.

Telehealth providers and direct-to-consumer platforms such as Lilly Direct, Ro, and Hims & Hers are also driving a surge in cash-pay purchases, according to Paytient CEO Brian Whorley. "We see a tripling from last year to this year of usage at GLP-1 oriented providers," he said, warning that affordability gaps risk leaving lower-income workers behind.

Employers are also pressing pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) to offer new drug payment models and considering alternative benefit managers who can negotiate directly with manufacturers, particularly for costly cell and gene therapies. "There are some new entities - some startups in this space - that are building out products and solutions where they are going on behalf of a pooled group of employers to negotiate with manufacturers," Kelsay said.

The rising costs come as many consumers are still grappling with high prices for essentials and sluggish wage growth. Last year, the average family premium for employer coverage was $25,572 - up 52% from a decade earlier - with employers paying roughly $19,000 and workers covering the remaining $6,000, according to KFF.