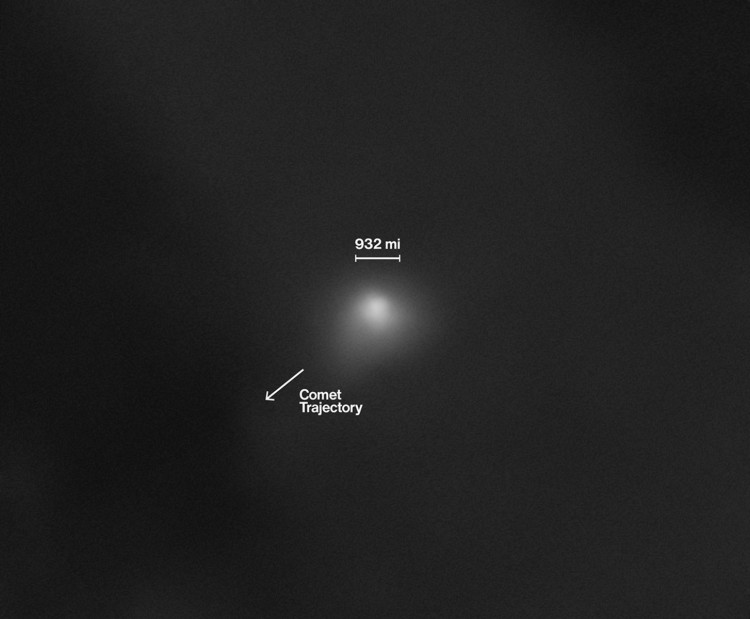

Newly released telescope images of the interstellar comet 3I/ATLAS have revealed what researchers describe as possible ice-volcanic eruptions, adding another layer of intrigue to one of the most unusual visitors to enter the inner solar system in modern observation. The findings, detailed in a study posted to arXiv, show plumes of gas, dust and frozen particles rising from beneath the comet's surface as it accelerates toward perihelion, behavior that has strengthened scientific interest in its origins and internal chemistry.

The activity, identified as cryovolcanism, appears to intensify as 3I/ATLAS is warmed by the Sun, producing a series of visible jets similar to those observed on distant icy bodies such as Pluto, Europa and Enceladus. Researchers said the eruptions help explain irregular patterns in earlier observations and point to subsurface pockets of volatile material destabilizing under solar radiation. These eruptions suggest layered internal structures and the preservation of primordial ices from the earliest eras of cosmic evolution.

Scientists estimate the object to be between 7 billion and 14 billion years old-meaning it likely predates the Sun. Its extreme age places 3I/ATLAS among the oldest materials ever documented passing through the solar system, offering scientists a rare opportunity to study compounds formed in a different star system and potentially under conditions that existed shortly after the Big Bang.

The study describes 3I/ATLAS as chemically rich, with spectral signatures resembling those of frozen bodies orbiting beyond Neptune. These similarities support theories that planetary systems across the galaxy may form Kuiper Belt-like regions, producing icy objects with comparable thermal and chemical histories. That link has helped refine models of how planets, moons and comets evolve both within and far beyond the solar system.

The detection of cryovolcanism on an interstellar object marks a first for planetary science, expanding the environments in which ice-volcano activity is known to occur. Until now, such eruptions had only been documented within the Sun's gravitational reach. The behavior of 3I/ATLAS supports existing hypotheses about how heat and pressure can drive eruptions even in extreme cold, demonstrating that interstellar bodies may follow similar physical processes despite originating in different star systems.

The observations have also renewed scientific debate about what ancient, erupting comets may reveal about early chemical development in the universe. While researchers stress there is no evidence of biological activity, the plumes from 3I/ATLAS release compounds that formed billions of years before the Sun-materials that could help scientists map the distribution of complex molecules across star-forming regions. These insights feed into broader discussions about prebiotic chemistry and how certain molecular building blocks may be transported between star systems.

Interest in the comet comes amid parallel studies into the chemical history of Earth and the solar system. Recent findings from Apollo samples and meteorite analyses show how ancient material can preserve records of planetary formation. The investigation of 3I/ATLAS serves as a complement to these efforts, offering an external point of comparison for understanding how early planetary bodies accumulate, store and disperse volatile compounds.