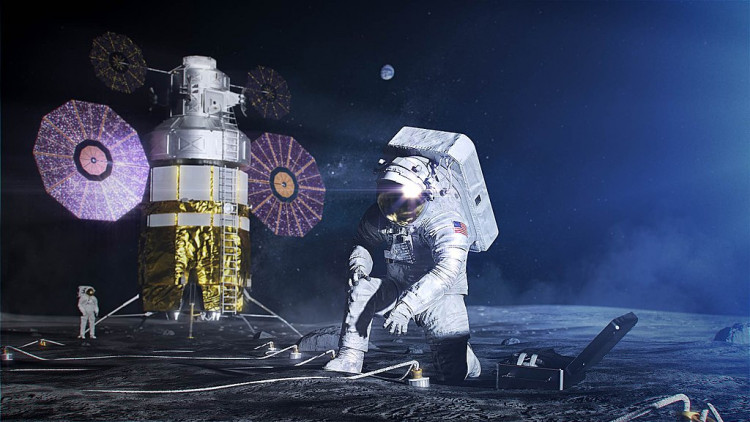

U.S. space agency NASA and seven other countries have signed the Artemis Accords, the unified guideline concerning the Artemis Program for crewed exploration of the moon.

In addition to the U.S., the United Kingdom, United Arab Emirates, Japan, Canada, Italy, Australia, and Luxembourg are now part of the project, whose goal is to return humans to the moon by 2024 and eventually establish a lunar base by 2030.

This may seem like an improvement. For a number of years, countries have argued with the issue of how to govern a human colony on the moon and deal with the handling of its resources. Yet a number of key countries are seriously worried about the agreement and have declined to sign them so far.

Previous efforts to govern space have come by multinational arrangements that have been closely negotiated. The Outer Space Treaty of 1967 laid down the fundamental rules for human space exploration, which should be peaceful and help all humanity, not just one country. But in the way of detail, the Treaty does nothing. The 1979 Moon Agreement sought to discourage commercial use of outer space resources, but it was ratified by only a limited number of nations, not by the U.S., China, and Russia.

Now that the US is enacting the Artemis Program, the question of how states will act in exploring the moon and using its resources has come to the fore. The signing of the accords is a major political attempt to codify and apply the key principles of space law to the program.

Russia has already declared that the Artemis Program is too "U.S.-centric" to be signed in its present form. The absence of China is clarified by the U.S. Congressional ban on collaboration with the country. Concerns that this is a seizure of power by the U.S. and its allies are exacerbated by the absence of any African or South American nations in the founding partner states.

Germany, France, and India are also unsettlingly missing. These are countries with well-developed space programs that would certainly have benefited from participation in the Artemis mission. Their resistance may be due to the preference for the moon agreement and the need to have a well-concluded treaty regulating the exploration of the moon.

As an organization, the European Space Agency (ESA) has not signed on to the accords either, but a number of ESA member states did. This is not unexpected. The aggressive US.. timeline for the project would run contrary to the lengthy consultation of the 17 member states needed for the ESA to sign as a whole.

In the end, the Artemis Accords is groundbreaking in the area of space exploration. A major shift in space governance is the use of bilateral arrangements that dictate codes of action as a prerequisite of inclusion in the program. With Russia and China opposing them, the agreements are likely to face diplomatic resistance, and their very presence can incite antagonism in conventional UN forums.