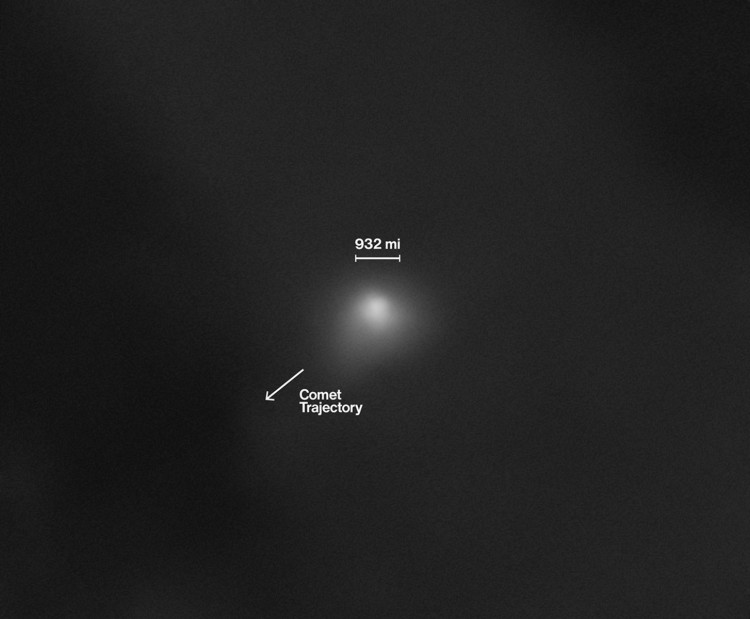

Astronomers are reassessing long-held theories of comet formation after new observations of the interstellar comet 3I/ATLAS revealed what researchers describe as unusually intense and widespread cryovolcanic activity. The object-only the third interstellar visitor ever detected-registered a sharp and sustained increase in brightness in 2025, prompting scientists to consider whether an eruption of volatile materials occurred across its surface as it moved within roughly 2.5 astronomical units of the Sun.

3I/ATLAS was first identified in July 2025 by the ATLAS telescope network and immediately drew interest for its hyperbolic trajectory and velocity, which peaked near 153,000 miles per hour. Its orbit, with an eccentricity of about 6.1, confirmed that it is not bound to the Sun. Its arrival marked the first such interstellar comet since 2I/Borisov in 2019, and the pristine condition of the object-untouched by previous stellar encounters-positioned it as a rare sample of unaltered material from beyond the Solar System.

Researchers who analyzed the brightness surge determined that the event was not a single explosive breakup but a prolonged eruption across the comet's outer water-ice layer. Their preprint argues that "a sharp and lasting surge" in light output, combined with the absence of fragmentation signs, strongly suggests cryovolcanism rather than surface shedding or collapse. This interpretation aligns with behaviour previously observed on icy moons such as Europa and Enceladus, though not at this scale on a comet.

The team, led by astronomers at Caltech and the University of Maryland, highlighted the comet's composition as a critical factor. Spectral analysis indicated similarities to carbonaceous chondrites-ancient meteorites notable for their organic richness and volatile minerals. The paper describes 3I/ATLAS as likely containing high concentrations of nickel and iron, an unusual metal load for a comet and a potential trigger for its eruptive behaviour.

According to the study, the warming near perihelion may have produced subsurface liquid that interacted with metal grains, driving corrosion and releasing energy. The resulting pressure, particularly from carbon dioxide gas "highly enriched in the comet's coma," could then push material through the porous ice crust, generating continent-scale cryovolcanism. The authors proposed that this mechanism, if verified, would require revisiting assumptions about the uniformity and low-metallicity structure of comets.

This interpretation also depends on the comet's lack of a protective dust mantle-common on long-period comets from the Oort Cloud-which can insulate surface layers and prevent wholesale activation. Without such a layer, even modest solar heating could trigger simultaneous eruptions across its surface.

"Each newly discovered object reveals unexpected properties that test and expand current models," the authors wrote, noting that interstellar examples provide unique insights into the physical and chemical processes that shape small bodies in other planetary systems. They added that "interstellar visitors like 3I/ATLAS continue to challenge and refine our understanding of planetary-system formation and the chemical evolution of small bodies."

The findings, still awaiting peer review, could have implications beyond this single object. If metal-driven cryovolcanism proves common in planet-forming regions elsewhere in the galaxy, it would raise questions about the diversity of materials incorporated into early comets and the thermal histories they may undergo even in star-free environments. As 3I/ATLAS moves back toward the outer reaches of the Solar System, researchers are continuing to monitor its fading coma to determine whether additional outgassing episodes emerge.