A dramatic new image from NASA's Hubble Space Telescope has intensified scientific debate around the disintegration of interstellar comet 3I/ATLAS, with Harvard astrophysicist Avi Loeb arguing that the object's striking 60,000-kilometre anti-tail extension aligns "in perfect agreement" with his prediction that the comet fragmented into numerous large bodies after its close brush with the sun. The observations come as U.S., European and Chilean observatories continue tracking the rare visitor-only the third confirmed interstellar object ever recorded-during its rapid exit from the Solar System.

The comet, officially designated 3I/ATLAS, was discovered July 1, 2025, by NASA's ATLAS survey telescope in Rio Hurtado, Chile. Scientists immediately identified its hyperbolic orbit and eccentricity of 6.13 as proof it was not gravitationally bound to the sun. Arriving from the direction of Sagittarius at roughly 58 km per second, the object approached Mars in early October before swinging around the sun on Oct. 30 in a brief perihelion passage that has triggered its accelerated disintegration.

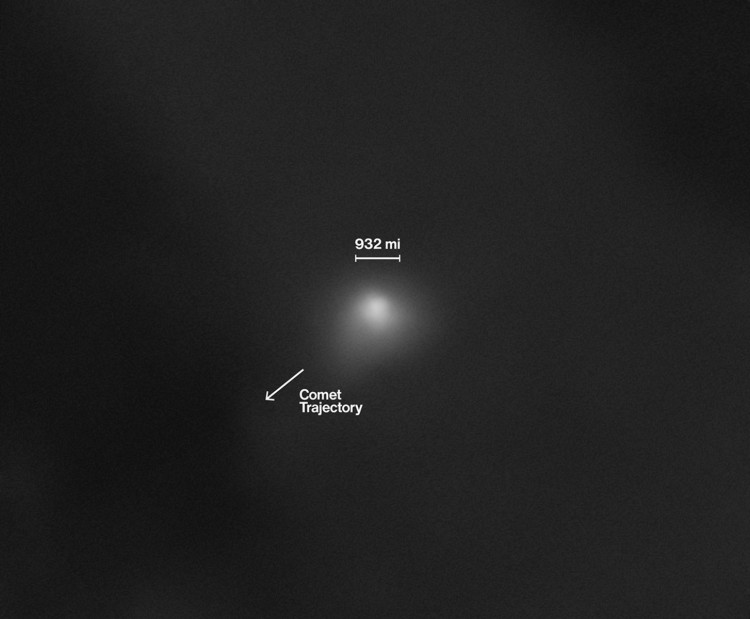

As researchers attempt to capture as much data as possible before the object disappears into deep space, Hubble's Wide Field Camera 3 has played a central role. A follow-up observation on Nov. 30 produced the sharpest view yet of the comet's coma-revealing a luminous, teardrop-shaped structure that narrows into a sunward anti-tail. NASA scientists said in their statement that "Hubble tracked the comet as it moved across the sky," adding that "As a result, background stars appear as streaks of light." The image is expected to guide several more months of outbound monitoring.

What distinguishes the new data is the extraordinary scale of the coma extension. Astronomers estimate the halo radius at about 40,000 kilometres, while the anti-tail extends roughly 60,000 kilometres toward the sun. That shape, according to Loeb, is evidence that the nucleus shed "a large number of macroscopic non-volatile objects" due to strong non-gravitational acceleration during perihelion. In his recent analysis, the physicist argued the fragments would separate from the main body by roughly that distance by late November-an estimate that he now notes "is in perfect agreement with the anti-tail extension of the teardrop shape in the new Hubble image."

The match between theory and observation has renewed interest in the physical structure of interstellar objects, particularly whether they behave differently from comets formed in the Solar System. Loeb has argued that 3I/ATLAS's behaviour-its asymmetric coma, its accelerating drift away from the sun, and its fragment dispersion-suggests a nucleus composed of unusually large, solid pieces rather than the volatile ices typical of conventional comets.

The stakes for astronomers are high. Interstellar visitors offer rare, direct samples of material from other star systems, and their compositions may reveal how planets form under radically different conditions. Only two such travellers have been observed previously: the cigar-shaped ʻOumuamua in 2017 and comet 2I/Borisov in 2019. Both ignited international debate, and 3I/ATLAS-whose elongated coma now provides a natural laboratory for observing disintegration in real time-has become the subject of similarly intense scrutiny.

The Hubble data arrives as 3I/ATLAS races toward a March 2026 pass by Jupiter at a distance of about 0.357 AU, after which it will accelerate into interstellar darkness. Each new image becomes a form of forensic documentation: a high-resolution record of the comet's physical breakdown as solar heating continues to strip away mass and expel debris.