Scientists observing the interstellar comet 3I/ATLAS are reporting unprecedented methane-related activity and carbon-rich chemistry, identifying a set of prebiotic molecules never before seen in an object from another star system. NASA researchers say the comet is releasing methanol at levels that dwarf those found in typical solar system comets, marking one of the most chemically unusual interstellar visitors ever recorded. The discovery offers new insight into how life-supporting molecules may form in distant planetary systems.

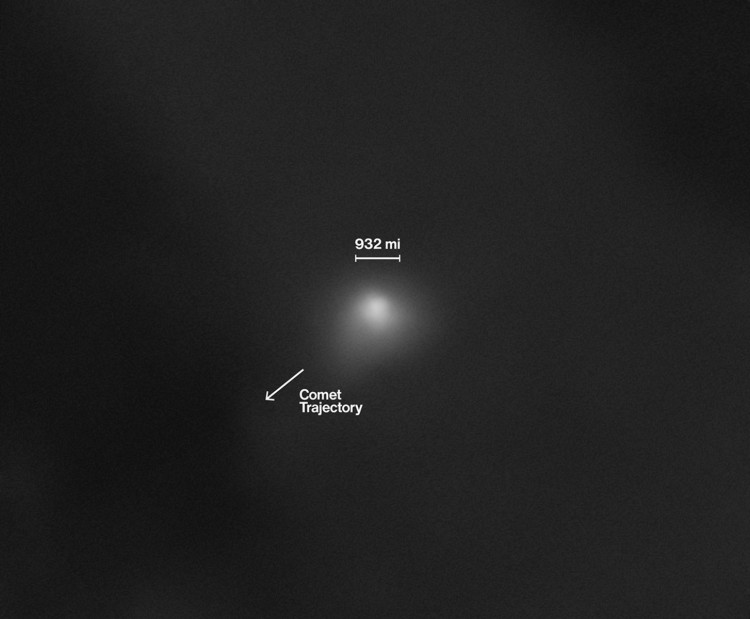

The comet-only the third known interstellar object, following 1I/'Oumuamua in 2017 and 2I/Borisov in 2019-was first detected in July 2025 by the ATLAS survey telescope in Chile. Early observations revealed a rapidly expanding cloud of water vapor and gas and an unusually high concentration of carbon dioxide. Its red-tinged appearance and early onset of outgassing suggested it had not passed near another star for hundreds of millions of years, preserving chemistry distinct from anything in the solar system.

To probe the object's volatile output, NASA's Martin Cordiner and his team at the Goddard Space Flight Center used the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA). They found unexpectedly high volumes of hydrogen cyanide and methanol-two compounds associated with complex chemical evolution. "Molecules like hydrogen cyanide and methanol are at trace abundances and not the dominant constituents of our own comets," Cordiner said. "Here we see that, actually, in this alien comet they're very abundant."

Hydrogen cyanide appears to be escaping directly from the comet's rocky nucleus at a rate of roughly 0.25 to 0.5 kilograms per second. Methanol production, however, is significantly higher. ALMA detected around 40 kilograms per second of methanol, accounting for about 8% of the comet's total vapor output-far above the roughly 2% typical in solar system comets. Methanol was observed both in the nucleus and in the comet's coma, indicating a complex chemical structure and potentially non-uniform interior.

These molecular disparities provide rare clues to how 3I/ATLAS formed. A nucleus producing different compounds from different regions suggests an accretion history unlike that of comets formed around the Sun. Cordiner noted that such abundance carries broader implications for astrobiology. "It seems really chemically implausible that you could go on a path to very high chemical complexity without producing methanol," he said, underscoring methanol's role as a precursor to more advanced organic molecules.

The findings also support a prediction by Josep Trigo-Rodríguez of the Institute of Space Sciences in Spain, who theorized that comets rich in metals like iron should release large amounts of methanol. Solar heating could melt internal ice and trigger reactions between liquid water and iron compounds, generating methanol as a byproduct. The unusually high methanol output from 3I/ATLAS may indicate a metal-rich nucleus, offering new evidence of how chemistry unfolds in other star systems.

For researchers, the comet represents an intact chemical time capsule from a distant, unknown origin. Its composition suggests that the building blocks of life-simple carbon-bearing molecules that contribute to prebiotic chemistry-are not confined to the solar system but are widespread across the Galaxy. The chemical profile of 3I/ATLAS, preserved over immense distances, provides a rare window into molecular processes unfolding light-years from Earth.