Newly released Justice Department records tied to the late Jeffrey Epstein offer an unusually granular view of his private medical concerns, including emails discussing hormone levels, sexually transmitted infections and a 2012 pitch offering "max p---- enlarger pills." The materials are part of a sweeping disclosure under a federal transparency law that opened millions of pages of documents while withholding categories meant to protect victims and exclude illegal content.

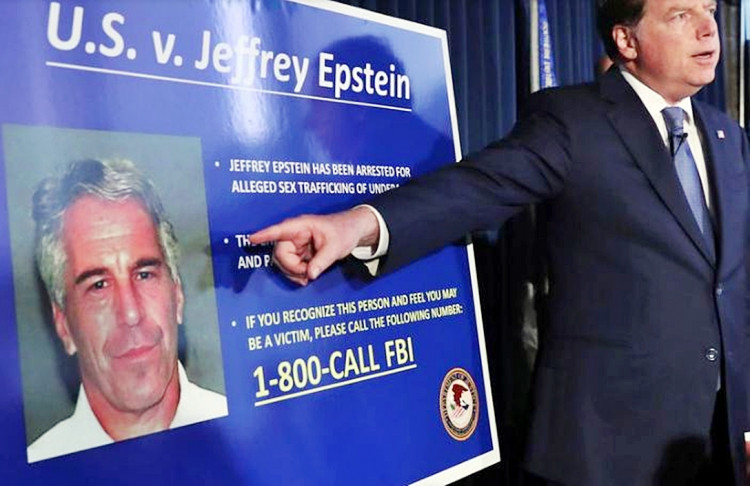

The cache, reviewed across multiple outlets, is not a single narrative but a collage of correspondence, lab results and physician exchanges. Epstein, who died in federal custody in 2019 while awaiting trial on sex-trafficking charges, appears less as a power broker than as an aging patient fixated on bodily control and quick solutions.

Among the records is a 2012 email sent by someone identifying himself as "Dr. Maxman," offering Epstein "max p---- enlarger pills." The files do not indicate whether Epstein purchased any product, but the solicitation itself underscores the transactional tenor that runs through the correspondence.

Other emails focus on hormone levels. Lab results cited in the records place Epstein's total testosterone at 142 nanograms per decilitre in 2014 and 125 ng/dL in 2017. For context, the American Urological Association says clinicians can use a total testosterone level below 300 ng/dL as a reasonable cut-off supporting a diagnosis of low testosterone.

The tone oscillates between self-diagnosis and urgency. In an August 2013 message, Epstein described nearly fainting and needing oxygen, adding: "Ghislaine came to help." He framed the episode as a hormonal crisis, writing: "I didn't want to worry you or involve you, as my testosterone levels, can't handle the stress."

By April 2015, Epstein expressed reluctance to begin hormone therapy, writing that his sleep was poor and that he was "hesitant" after living with low testosterone for 15 years. A year later, after trying medication akin to Clomid at a physician's suggestion, he reversed course, calling starting it a "giant mistake."

The documents also show Epstein seeking treatment for infections. In a 2016 email to New York physician Jay Lombard, he wrote that tests showed "some gc" in semen and detailed antibiotics taken-"1 gram ceftriaxon and 2 g azithromycin"-after a blood test indicating gonococcus. He listed parasites, blood in urine and a history of bladder polyps, then closed with a pointed appeal: "Sherlock? how can we work together?"

Lombard replied with clinical suggestions, advising testing for a C1 inhibitor deficiency and writing it was what he suspected "may be the culprit" behind several symptoms. Elsewhere, Epstein's correspondence with physician Bruce Moskowitz tracks his ongoing anxiety over hormone management.

Some survivor accounts, cited in court filings and media reports, include descriptions of Epstein's genitalia-one accuser described it as "more of the shape of a lemon" and "really small" when erect-and similar language appears in James Patterson's 2016 book Filthy Rich. The records' medical minutiae, however, sit uneasily beside the broader allegations, highlighting how routine health complaints and entitlement coexisted with conduct prosecutors described as criminal.