Three previously thought-to-be-confirmed exoplanets have since been disproved, while a fourth is under critical doubt.

The objects Kepler-854b, Kepler-840b, and Kepler-699b appear to be too massive to be exoplanets after all, according to a new analysis using revised characteristics. That suggests that they could be stars. Kepler-747b, the fourth object, is a borderline situation that may require more evidence to resolve.

The distinctions between the masses of planets and stars can be a little hazy, with considerable overlap, but there are limitations. Objects grow too small below a certain size to achieve the core pressure and temperature required to spark the hydrogen fusion that lights a star. Over a particular threshold, an object must be a star of some kind.

"Most exoplanets are Jupiter-sized or much smaller," astronomer Prajwal Niraula of MIT, who led the study, explained. "Twice [the size of] Jupiter is already suspicious. Larger than that cannot be a planet."

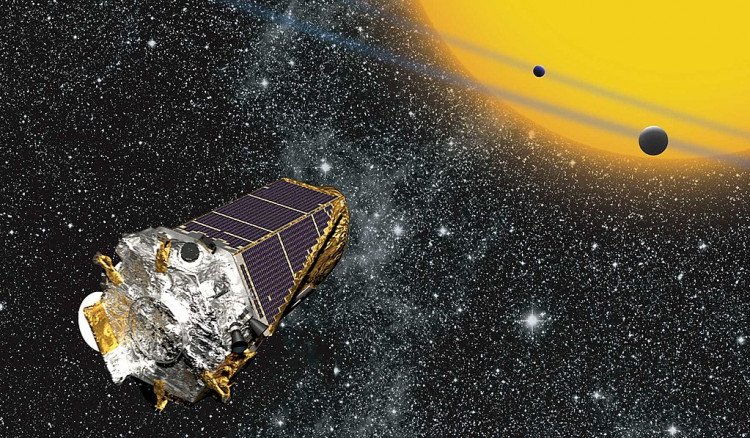

The Kepler planet-hunting telescope, which has since retired in October 2018, looked for transits to find exoplanets. When an exoplanet passes between us and its home star, it causes small dips in starlight on a regular basis. This causes a 'transit curve' in the star's light, allowing astronomers to estimate the exoplanet's size.

The Milky Way is being redefined thanks to a project called Gaia. Gaia is charting the precise position and motion of Milky Way stars in three-dimensional space with the highest accuracy ever using stellar parallax. When Kepler-854b was identified in 2016, there were no Gaia data for its host star.

However, they are now; when Niraula and colleagues reviewed the exoplanet's features using updated Gaia data, they discovered the exoplanet was significantly larger than previously thought, roughly three times the size of Jupiter. They also computed its mass, which is around 239 times that of Jupiter; the highest limit for a planet's mass is approximately 10 Jupiters.

"There's no way the Universe can make a planet of that size," astrophysicist Avi Shporer of MIT's Kavli Institute for Astrophysics and Space Research said. "It just doesn't exist."

The team believes that now that the issue has been identified, there are unlikely to be many more small stars out there masquerading as confirmed exoplanets. We may be more certain that exoplanets are exoplanets now that we have a wealth of Gaia data at our disposal and are aware of the situation.

The research has been published in The Astronomical Journal.