The Kessler Syndrome is named after Donald Kessler, a former NASA scientist who first proposed the concept in a landmark 1978 paper.

Kessler and co-author Burton Cour-Palais highlighted in their paper, "Collision Frequency of Artificial Satellites: The Creation of a Debris Belt," that the chance of satellite collisions grows as more spacecraft are lofted into orbit. And each of these collisions would have a massive effect on the orbital environment.

The problem is, when objects are traveling across space, even a tiny paint chip can shatter glass or steel. Debris fragments essentially become bullets.

What Kessler anticipated was that objects in low-earth orbit would collide sooner or later, causing chain reactions similar to billiard balls colliding on a crowded pool table.

If a piece of junk collides with a satellite, it creates more debris, which increases the chance of further collisions... and so on. You might hit a tipping point at some moment. Because there would be so much debris, collisions would be unavoidable, turning low-earth orbit into a junkyard where no satellites would be able to survive.

According to the European Space Agency (ESA), humanity has launched approximately 12,170 satellites since the commencement of the space age in 1957, with 7,630 remaining in orbit today - but only roughly 4,700 of them are still operational.

That means approximately 3,000 defunct spacecraft, as well as other large, deadly bits of debris like upper-stage rocket bodies, are speeding about Earth at incredible speeds. For instance, orbital velocity at 250 miles altitude, where the ISS flies, is around 17,100 miles per hour.

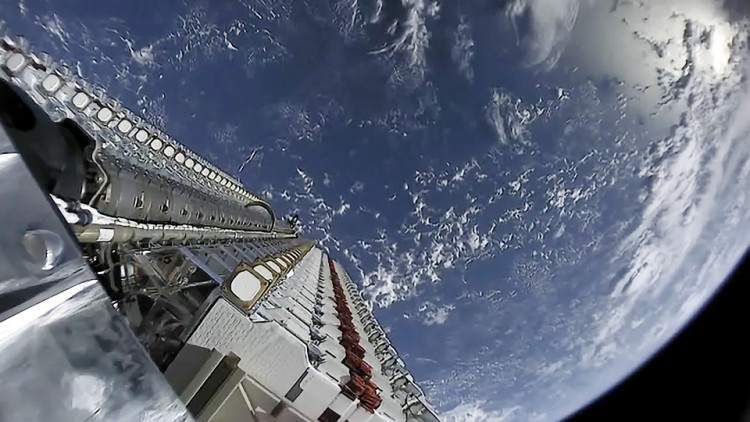

Not just because of the jolts provided by the Chinese ASAT test and the Iridium-Kosmos crash, the space community is taking the threat of orbital debris more seriously these days. Multiple satellite "megaconstellations" are in the works (for example, SpaceX's Starlink), making space traffic management and space junk mitigation more urgent than ever.

The Space Safety Coalition (SSC) proposed a set of voluntary guidelines in 2019 to keep the Kessler Syndrome, as well as space junk in general, at bay in the coming years.

All satellites operating over 250 miles should be equipped with propulsion systems that allow them to navigate away from potential collisions, according to one recommendation. According to the SSC, drawing the line there makes sense for a variety of reasons: it's the altitude at which the ISS flies, and satellites that circle below it tend to face enough atmospheric pull to fall out of orbit very soon after their operational lives expire.

The SSC also advises satellite designers to incorporate encryption systems into their craft's command systems, making them more difficult to hijack by chaos-seeking hackers. Operators of low-earth-orbit satellites should include a requirement in their launch contracts that rocket upper stages be discarded in the atmosphere shortly after liftoff.