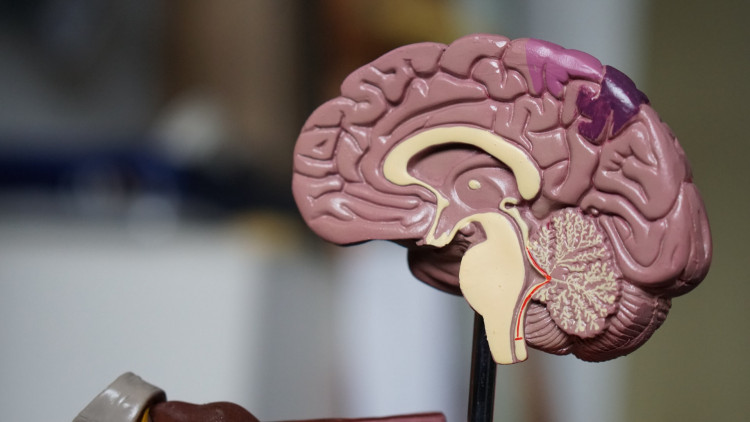

How do the brains of advanced physicists manage to delve into worlds too impossible to comprehend?

Researchers at Carnegie Mellon University have discovered a mechanism to decipher the brain activity linked with individual abstract scientific notions relevant to matter and energy, such as fermion or dark matter, in a report recently published in npj: Science of Learning.

CMU's Robert Mason, senior research associate, Reinhard Schumacher, professor of physics, and Marcel Just, the D.O. Hebb University Professor of Psychology, used functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to record the thought processes of their fellow physics faculty members regarding advanced physics concepts.

The purpose of this research was to figure out how the brain organizes very abstract scientific ideas. How does a physicist's brain organize knowledge? An encyclopedia organizes knowledge alphabetically, a library organizes it according to something like the Dewey Decimal System, but how does a physicist's brain organize knowledge?

The researchers wanted to see if the activation patterns elicited by distinct physics concepts might be categorized based on concept features. One of the most surprising findings was that the physicists' minds classified the notions into those that were measurable and those that were immeasurable in size.

For the most part, everything tangible on Earth can be measured with the correct ruler, scale, or radar gun. However, other notions, like dark matter, neutrinos, and the multiverse, are immeasurable to physicists. The measurable and immeasurable notions are organized separately in the minds of physicists.

These thoughts didn't show up in the brain scans as "extent" activity, which he roughly defines as putting tangible constraints on something.

The team concluded that physicists' brains instinctively distinguish between abstract concepts like quantum physics and comprehensible, measurable concepts like velocity and frequency.

Basically, the stuff that perplexes us non-physicists does not generate notions of "extent" for them. That's why they can presumably think about those things with relative ease, whereas we start worrying about scale.

Just, one of the authors, highlights how the brain evolves to accept new, abstract ideas in all of us. Perhaps only theoretical physicists can grasp duality or a multiverse, but people in other professions, of course, explore complicated ideas as well.